Collab Fund

As a prominent capital source for forward-thinking entrepreneurs, Collab Fund encourages innovation that paves the way for a better world.

Outrunning Giants: Building in OpenAI’s Shadow

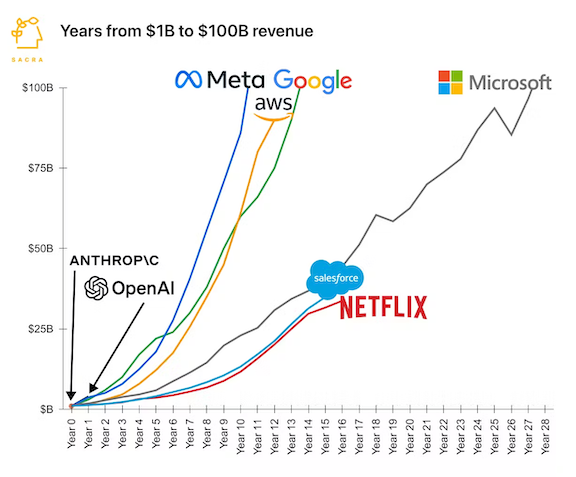

From 2016-2021, a flurry of writing assistants, conversational chatbots, travel booking platforms, and meeting transcription tools popped up on the AI scene, many growing at breakneck paces.

And then along came ChatGPT’s steady rollout of new features: from freemium chatbots and writing tools in 2021 to, the release of Operator for booking in January 2025, and Record mode for meeting transcription in June 2025 — putting real strain on startups trying to compete.

This is a refrain I hear over and over in consumer AI investing: how can you build consumer applications when OpenAI has such a lion’s share of user attention (and data) to build any tool it wants.

When a single company begins to dominate a category, the instinct is to copy or cave. But the correct move is to find the spaces where the behemoth can’t compete. Where its own size might work against it. During Web 2.0, Google was that behemoth, bulldozing everything from Yahoo and MapQuest to AltaVista and AskJeeves. Still, e-commerce and social carved out their own ground beyond Google’s grasp.

Now OpenAI towers in consumer AI with hundreds of millions of weekly users and vast compute at its back. So where might value accrue outside its shadow?

The Gravity of the Giant

OpenAI’s ChatGPT has become a default destination for anyone exploring what consumer AI can do. Its freemium launch hit 1 million users in days and reached a record breaking 100 million MAUs in just two months.

What’s even more remarkable is the retention: over 80% of active users return regularly, and paid subscribers show retention north of 70% after six months.

That level of attention fuels personalization: the more you use it, the more it learns your patterns, preferences, and shortcuts. It’s human nature to stick with what feels familiar, but the ever-improving feedback loop of AI only magnifies that tendency. Consumer apps face both OpenAI’s head start and this natural stickiness. But just as Google could not put up a fight against Amazon and Facebook, there are areas where startups have the edge. Here are the three that I’m paying close attention to:

1. Vertical Trust and Domain Expertise

General-purpose chatbots struggle with high-stakes, regulated domains. Imagine asking for tax advice or mental health guidance from a generic model: liability concerns and nuanced regulations demand specialized expertise. In personal finance, healthcare, taxes, real estate and other fields built on trust, users need evidence of domain credibility. A startup that embeds clinicians, registered accountants, or licensed advisors into an AI workflow can differentiate.

The model may handle surface-level queries, but the human-vetted pipeline or validated data sources create a barrier OpenAI alone cannot clear without replicating specialized teams. It’s a classic dyanmic, but deep verticals reward focused players more than horizontal giants.

2. Bridging to the Physical World

As powerful as AI is, many high-value consumer experiences still benefit from (or even require) real-world integration. Startups like Doctronic show how AI triage leads to a telehealth session, then perhaps to in-person care. Travel can be reimagined: an AI plans an itinerary, but it also books local experiences, arranges guides, or curates surprise pop-ups — and then follows you there. Real estate might not just match listings and orchestrating visits, but guide you in real time through inspections, paperwork, and move-in services.

These require logistics, partnerships, and on-the-ground networks. The moat isn’t the model; it’s the operational backbone that connects AI suggestions to tangible outcomes. That’s a hard feat for a digital-first (and only) company like OpenAI.

3. Closing the Creativity Gap

A June 2025 study in Nature Human Behaviour investigated brainstorming tasks where participants used tools like ChatGPT versus relying on their own ideation plus web searches. It found that while AI can boost idea quantity, it often reduces variety: many AI-assisted participants produced very similar concepts, suggesting a “creativity gap” in generative models compared to unfettered human thinking. This echoes concerns that AI’s training on large but finite datasets drives convergence toward statistically common patterns, limiting novelty despite fluent output. Enhancing human creativity, mimicking human creativity will be tremendous efforts requiring specialized teams that think creatively themselves, and not just technically.

This isn’t to dismiss LLMs’ value (accelerating first drafts can meaningfully improve the creative process) but genuine creativity demands human curation, oddball connections, and serendipity. Startups that build tools to surface unexpected prompts, aggregate diverse human inputs, or structure hybrid workshops can capture value where vanilla AI falters.

Final Thoughts

It’s easy to feel outgunned by OpenAI’s budget and reach when single new feature release can eclipse months of effort. But success isn’t’ about trying to outscale OpenAI. It’s about finding places where AI is a means to something bigger. Giants excel at horizontal scale, but stumble on deep trust, real-world execution, or genuine novelty. That’s where value will continue to accrue. In the gaps that AI can’t fill.

Checklist for founders:

-

Trust gap: Which regulated domain do you know deeply? How will you embed vetted experts and compliance into your workflow?

-

Physical integration: What real-world services or partnerships can you build that a digital-first giant would find expensive to replicate?

-

Creative differentiation: How will you inject human serendipity or domain-specific inputs before or alongside AI to surface truly novel ideas?

-

Operational moat: What processes, partnerships, or data pipelines can you lock in early to defend against copycats?

-

User habit loops: How will you create feedback loops (e.g., personalized data, rewards) that cement engagement beyond a generic model’s appeal?

Lately, it feels like every corner of my internet bubble is talking about venture returns—Carta charts one day, leaked DPI tables the next. I’ve seen posts on lagging vintages, mega-fund bloat, the “Venture Arrogance Score”, the rising bar for 99th‑percentile exits, and the PE-ification of VC.

But for all that noise, I haven’t seen much that actually walks through how returns metrics evolve over time in an early-stage fund. That’s a crucial gap. Many analyses focus on funds that are still mid-vintage, where paper markups can tell an incomplete or even misleading story.

So I pulled the numbers on Collaborative’s first fund, a 2011 vintage that’s now nearly fully realized. It offers a concrete look at how venture performance can unfold across a fund’s full lifecycle.

Fund 1 was small: $8M deployed across 50 investments. Check sizes ranged from ~$10K to ~$400K, averaging around $100K for both initial and follow-on rounds. It was US-focused, sector-agnostic, and mostly pre-seed through Series A.

Portfolio metrics

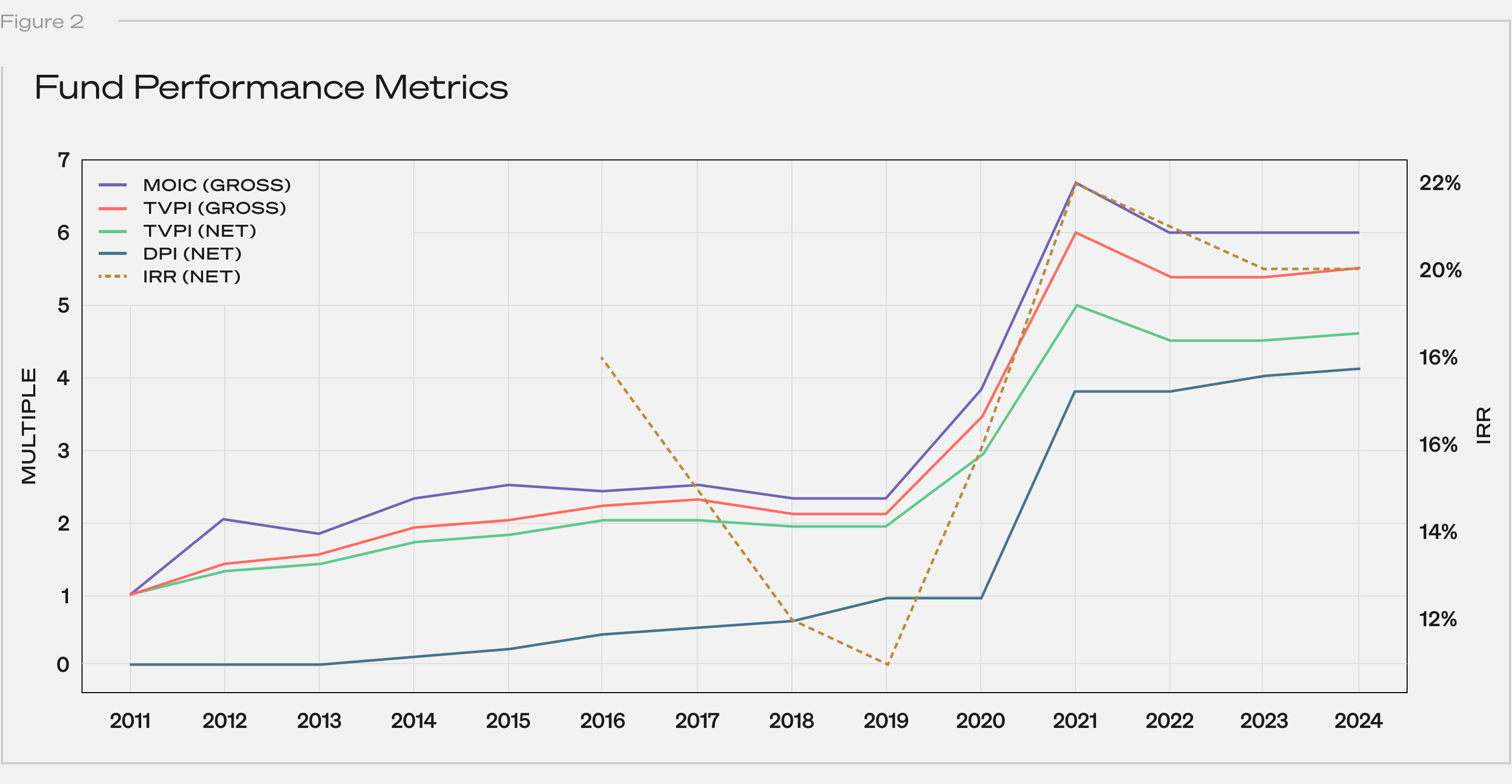

Without further ado, here’s how the fund performed over its lifetime across a few core metrics:

Note: Distributions are net to LPs; contributions reflect paid-in capital. IRR data was not meaningful (“NM”) for years 1–5.

Below is a line chart of the returns data:

Note: IRR is shown as a dashed line corresponding to the secondary axis.

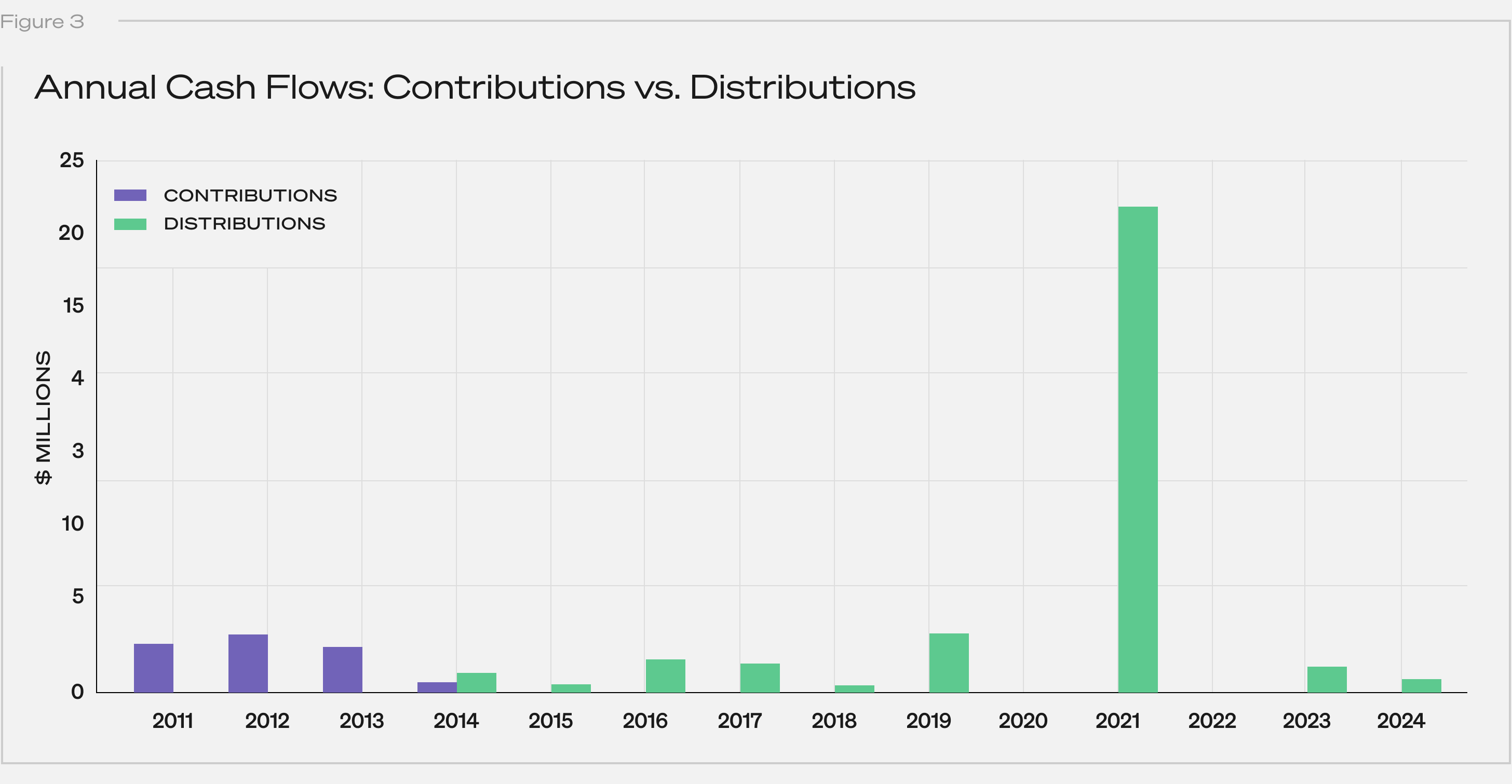

Contributions wrapped up by year 4, which is typical for early-stage funds. Distributions didn’t start until year 4 and peaked around year 10:

Returns metrics takeaways

- Strong overall performance: The fund achieved a 4.1x net DPI—solidly top-decile. For context, PitchBook pegs 3.0x as the 90th percentile for funds in the 2011 vintage.

- The patience premium: At year 10, DPI was 0.9x. There’s a lot of discussion right now around the lack of venture liquidity. 10 years in, this fund could’ve been a talking point. But then, in year 11, DPI jumped to 3.8x. Liquidity might be slow, but value can still be building.

- The IRR roller coaster: Net IRR hit 18% in year 6 (off paper gains), sagged in the middle years, then popped to 22% in year 11 after a major exit. IRR can be hurt by delays, even when final outcomes are strong.

- Some juice still left: Even after 14 years, the fund sits at 4.1x net DPI and 4.6x net TVPI. That means roughly 0.5x of upside is unrealized. That tees up the classic end‑of‑life question: seek to harvest the tail or ride it out?

- Shallow J-curve: Early markups lifted TVPI above 1x by Year 2, keeping LPs above water on paper even before distributions began.

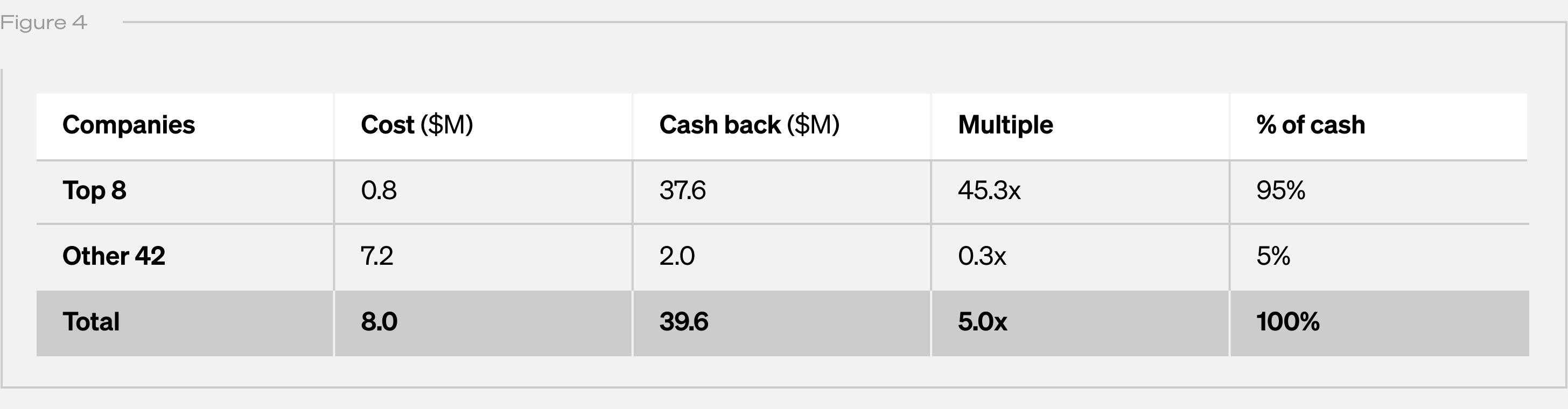

Where did the DPI actually come from?

Returns were highly concentrated. Eight companies—Upstart, Lyft, Scopely, Blue Bottle Coffee, Maker Studios, Gumroad, Reddit, and Kickstarter—drove nearly all distributions.

Note: “Cost” is cumulative capital actually invested. “Cash Back” is cumulative proceeds received by the fund from realization events, and excludes (i) any remaining unrealized value and (ii) fund-level fees and expenses. “Multiple” is the quotient of Cash Back divided by Cost.

Together, these accounted for just $0.8M of invested capital but returned $37.6M—an average multiple of 45x. The remaining 42 investments, representing $7.2M, returned only $2.0M (a 0.3x multiple).

Within those eight, outcomes varied widely: one company alone delivered 73% of all cash returned. Adding the next three brought the cumulative share past 90%. Multiples ranged from 1.4x to 115x—illustrating just how concentrated and variable even a “winning” subset can be.

Portfolio lessons

- Power law: Eight companies drove ~95% of all returns. One contributed 73% on its own.

- Capital efficiency: Less than $1M into the top eight generated $37.6M back.

- Check size ≠ upside: Some of the biggest winners were sub-$100K checks, while some larger bets in the tail went to zero. Limiting ticket size can cap downside without necessarily hampering fund performance.

- Winner variance: Even among the winners, multiples ranged from low single digits up to well over 100x, underscoring that not every winner needs to be a moonshot but a few big outliers can matter tremendously.

Conclusion

We believe the biggest risk in early-stage VC isn’t failure. It’s missing (or mis-sizing) the outlier. In Fund I, eight companies drove nearly all distributions. One check alone accounted for more than 70% of DPI. This is the power law at work.

Collaborative’s story now spans 15 years with four early funds in harvest mode. Three rank in PitchBook’s top quartile with two in the top decile by DPI. In each, a small number of companies drove the bulk of returns. Perhaps these will make for future posts.

Until then, I hope this serves as a reminder to take venture performance narratives based on unrealized funds with a grain of salt. Some trends are real and worth watching. But many of the loudest signals may fade or reverse as funds mature. Until they’re fully played out, their stories are still being written.

Disclaimer: 1. This post is for illustrative purposes only. Certain statements contained herein reflect the subjective views and opinions of Collaborative Fund Management LLC (“Collab”). Such statements cannot be independently verified and are subject to change. In addition, there is no guarantee that all investments will exhibit characteristics that are consistent with the initiatives, standards, or metrics described herein. Certain portfolio companies shown herein are for illustrative purposes only and are a subset of Collab investments. Not all investments will have the same characteristics as the investments described herein. It should not be assumed that any investments identified and discussed herein were or will be profitable. 2. Certain information contained in this post constitutes “forward-looking statements” that can be identified by the use of forward-looking terminology such as “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “target,” “project,” “estimate,” “intend,” “continue,” or “believe” or the negatives thereof or other variations thereon or comparable terminology. Due to various risks and uncertainties, actual events or results or the actual performance of any Collab investment may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. 3. Performance as of December 31. 2024, unless otherwise noted. Past performance is not indicative of future results. There can be no assurance that any Collab investment or fund will achieve its objective or avoid substantial losses. Gross returns do not reflect the deduction of management fees, carried interest, expenses and other amounts borne by the investors, which will reduce returns and in the aggregate are expected to be substantial. References to “Net IRR” are to the internal rate of return calculated at the fund level. In addition, references to “Net IRR”, “Net TVPI” and “Net DPI” are calculated after payment of applicable management fees, carried interest and other applicable expenses. Internal rates of return are computed on a “dollar-weighted” basis, which takes into account the timing of cash flows, the amounts invested at any given time, and unrealized values as of the relevant valuation date. 4. The values of unrealized investments are estimated as of December 31. 2024, are inherently uncertain and subject to change. There is no guarantee that such value will be ultimately realized by an investment or that such value reflects the actual value of the investment. Actual realized proceeds on unrealized investments will depend on, among other factors, future operating costs, the value of the assets and market conditions at the time of disposition, any related transaction costs and the timing and manner of sale, all of which may differ from the assumptions on which the valuations reflected in the historical performance data contained herein are based. Accordingly, the actual realized proceeds on these unrealized investments may differ materially from the returns indicated herein and there can be no assurance that these values will ultimately be realized upon disposition of investments. Different methods of valuing investments and calculating returns may also provide materially different results. 5. For informational purposes only. Not a public solicitation. 6. References to performance rankings of the fund herein refer to PitchBook’s Venture Capital Benchmark rankings for all geographies and fund sizes with data as of Q4 2024.

Collaborative Fund recently launched AIR, a new kind of accelerator for design-led AI products. It draws inspiration from the institutions that reshaped creative possibility in their time, places that brought together unlikely collaborators at key moments of technological and cultural inflection.

As we recruit for the first cohort, we’re talking to people who had a hand in creating those lighting rod moments. A few weeks ago we asked Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab, to reflect on what happens when culture and technology collide to create new ways of thinking.

Today we’re talking to Tom McMurray, former General Partner at Sequoia, who helped shape Silicon Valley’s first golden age. Tom was an early investor in Yahoo, Redback Networks, C-Cube, NetApp—and, importantly, Nvidia. He now serves on multiple boards focused on science and impact. We spoke to him about pattern recognition, capital discipline, and why he’s an investor in AIR.

Craig Shapiro: Tom, you joined Sequoia just as the first Internet wave was forming. Your portfolio reads like a Hall of Fame roster. What were the core filters you used back then?

Tom McMurray: It was very clear where to invest in the networking space—bandwidth was in high demand. It was less clear in the pure Internet space. Our diligence process was pretty established so we continually developed more refined filters and leveraged off our core capability in chips and enterprise software. In the case of Nvidia we had what I call a Sequoia moment—that wonderful nonlinear diligence process where after parsing through the business, we reached a point where there’s only a single question left to decide. Our secret sauce was that we often knew many times more than the founders did about their business. We understood where the real risks were.

For companies like Nvidia, our expertise in semiconductors from investments in Cypress, Microchip, LSI Logic, and Cadence, plus our experience with gaming companies, meant the market risks were very low. We could easily do due diligence on the founders because many worked for friends of Sequoia Partners—this was our sweet spot in the 1990s. And in the Internet wave, we had special insight through our investments in Cisco and Yahoo. They were market pioneers who saw the world 3-5 years ahead of us. They pointed the way many times, and we just jumped on it.

Speaking of Nvidia, walk us through what happened when Jensen Huang first pitched Sequoia.

Wilf Corrigan, a Sequoia Technology Partner and CEO at LSI Logic (where Jensen worked before starting Nvidia), told him to talk to Don Valentine at Sequoia about his “chip idea.” Jensen pitched the evolving game world and the need for more performance. Honestly, I had no idea at that point why we should invest in the company. But we asked harder and harder questions about team, competition, distribution, and got solid answers.

About 90 minutes into the pitch, Pierre Lamond asked Jensen how big the chip was. Jensen said “12 mm.” Pierre looked at Don and Mark; they nodded, and we committed to the investment on the spot. We led the Series A and Mark joined the board. The rest is history.

The critical question wasn’t about market size or vision—it was “can they build the chip, get the performance, and the price point?” That’s why the chip size question was the deciding factor. The semiconductor partners at Sequoia—Don, Pierre, and Mark—understood the significance immediately.

Fast-forward to today. Collaborative Fund just launched AIR, an AI residency in New York. You are an investor! Why?

Because you’re reproducing the conditions that made Sequoia’s hallways electric in the ’90s—cross-pollination of builders, researchers, and designers who argue, prototype, and iterate in the same room. Great companies are rarely solo acts; they’re jazz ensembles riffing toward a common groove.

What early-stage pattern recognition from Sequoia days should our AIR founders tattoo on their whiteboards?

The secret is to lean on your wins, learn from them, apply it as you expand, iterate, and keep going.

“Stay cheap until it hurts.” Capital efficiency forces clarity. The companies that survived the dot-com crash had burn rates lower than their Series A checks.

Critics worry AI will erase jobs or amplify bias. You’ve seen every tech cycle: where’s your compass pointing?

Every wave starts messy. But history says two truths persist:

-

Jobs evolve faster than they evaporate. Cisco killed some circuit-switch jobs yet birthed the entire network-engineer class.

-

Bias follows data, not silicon. Fix the training data, and you fix 80 percent of the problem. That’s human homework, not machine destiny.

The “force for good” part kicks in when entrepreneurs bake guardrails into the business model, not just the codebase.

Last one. A founder walks into AIR with nothing but conviction. You’ve got one question before you decide to invest—what is it?

I’d look for that “Sequoia Moment”—where after all the questions about team, market, and technology, we identify the single critical factor that determines success. For Nvidia, it was “how many millimeters wide is the chip?” Sometimes, it’s these seemingly simple technical questions that reveal whether a company can execute on its vision.

Golden. Thanks, Tom. Here’s to building AI companies that deserve to exist.

And to founders who remember: progress isn’t inevitable—people make it so.

A boy once asked Charlie Munger, “What advice do you have for someone like me to succeed in life?” Munger replied: “Don’t do cocaine. Don’t race trains to the track. And avoid all AIDS situations.”

It’s often hard to know what will bring joy but easy to spot what will bring misery. Building a house is complex; destroying one is simple, and I think you’ll find a similar analogy in most areas of life. When trying to get ahead it can be helpful to flip things around, focusing on how to not fall back.

Here are a few pieces of very bad advice.

Allow your expectations to grow faster than your income

Envy others’ success without having a full picture of their lives.

Pursue status at the expense of independence.

Associate net worth with self-worth (for you and others).

Mimic the strategy of people who want something different than you do.

Choose who to trust based on follower count.

Associate engagement with insight.

Let envy guide your goals.

Automatically associate wealth with wisdom.

Assume a new dopamine hit is a good indication of long-term joy.

View every conversation as a competition to win.

Assume people care where you went to school after age 25.

Assume the solution to all your problems is more money.

Maximize efficiency in a way that leaves no room for error.

Be transactional vs. relationship driven.

Prioritize defending what you already believe over learning something new.

Assume that what people can communicate is 100% of what they know or believe.

Believe that the past was golden, the present is crazy, and the future is destined for decline.

Assume that all your success is due to hard work and all your failure is due to bad luck.

Forecast with precision, certainty, and confidence.

Maximize for immediate applause over long-term reputation.

Value the appearance of looking busy.

Never doubt your tribe but be skeptical of everyone else’s.

Assume effort is rewarded more than results.

Believe that your nostalgia is accurate.

Compare your behind-the-scenes life to others’ curated highlight reel.

Discount adaptation, assuming every problem will persist and every advantage will remain

Use uncertainty as an excuse for inaction.

Judge other people at their worst and yourself at your best.

Assume learning is complete upon your last day of school.

View patience as laziness.

Use money as a scorecard instead of a tool.

View loyalty (to those who deserve it) as servitude.

Adjust your willingness to believe something by how much you want and need it to be true.

Be tribal, view everything as a battle for social hierarchy.

Have no sense of your own tendency to regret.

Only learn from your own experiences.

Make friends with people whose morals you know are beneath your own.

“The older I get the more I realize how many kinds of smart there are. There are a lot of kinds of smart. There are a lot of kinds of stupid, too.”

– Jeff Bezos

The smartest investors of all time went bankrupt 20 years ago this week. They did it during the greatest bull market of all time.

The story of Long Term Capital Management is more fascinating than sad. That investors with more academic smarts than perhaps any group before or since managed to lose everything says a lot about the limits of intelligence. It also highlights Bezos’s point: There are many kinds of smarts. We know – in hindsight – the LTCM team had epic amounts of one kind of smarts, but lacked some of the nuanced types that aren’t easily measured. Humility. Imagination. Accepting that the collective motivations of 7 billion people can’t be summarized in Excel.

“Smart” is the ability to solve problems. Solving problems is the ability to get stuff done. And getting stuff done requires way more than math proofs and rote memorization.

A few different kinds of smarts:

1. Accepting that your field is no more important or influential to other people’s decisions than dozens of other fields, pushing you to spend your time connecting the dots between your expertise and other disciplines.

Being an expert in economics would help you understand the world if the world were governed purely by economics. But it’s not. It’s governed by economics, psychology, sociology, biology, physics, politics, physiology, ecology, and on and on.

Patrick O’Shaughnessy wrote an email to his book club years ago:

Consistent with my growing belief that it is more productive to read around one’s field than in one’s field, there are no investing books on this list.

There is so much smarts in that sentence. Someone with B+ intelligence in several fields likely has a better grasp of how the world works than someone with A+ intelligence in one field but an ignorance of that field just being one piece of a complicated puzzle.

2. A barbell personality with confidence on one side and paranoia on the other; willing to make bold moves but always within the context of making survival the top priority.

A few thoughts on this:

“The only unforgivable sin in business is to run out of cash.” – Harold Geneen

“To make money they didn’t have and didn’t need, they risked what they did have and did need. And that is just plain foolish. If you risk something important to you for something unimportant to you, it just doesn’t make any sense.” – Buffett on the LTCM meltdown.

“I think we’ve always been afraid of going out of business.” – Michael Moritz explaining Sequoia’s four decades of success.

A key here is realizing there are smart people who may perform better than you this year or next, but without a paranoid room for error they are more likely to get wiped out, or give up, when they eventually come across something they didn’t expect. Paranoia gives your bold bets a fighting chance at surviving long enough to grow into something meaningful.

3. Understanding that Ken Burns is more popular than history textbooks because facts don’t have any meaning unless people pay attention to them, and people pay attention to, and remember, good stories.

A good storyteller with a decent idea will always have more influence than someone with a great idea who hopes the facts will speak for themselves. People often wonder why so many unthoughtful people end up in government. The answer is easy: Politicians do not win elections to make policies; they make policies to win elections. What’s most persuasive to voters isn’t whether an idea is right, but whether it narrates a story that confirms what they see and believe in the world.

It’s hard to overstate this: The main use of facts is their ability to give stories credibility. But the stories are always what persuade. Focusing on the message as much as the substance is not only a unique skill; it’s an easy one to overlook.

4. Humility not in the idea that you could be wrong, but given how little of the world you’ve experienced you are likely wrong, especially in knowing how other people think and make decisions.

Academically smart people – at least those measured that way – have a better chance of being quickly ushered into jobs with lots of responsibility. With responsibility they’ll have to make decisions that affect other people. But since many of the smarties experienced a totally different career path than less intelligent people, they can have a hard time relating to how others think – what they’ve experienced, how they see the world, how they solve problems, what kind of issues they face, what they’re motivated by, etc. The clearest example of this is the brilliant business professor whose brain overlaps maybe a millimeter or two with the guy successfully running a local dry cleaning business. Many CEOs, managers, politicians, and regulators have the same flaw.

A subtle form of smarts is recognizing that the intelligence that gave you the power to make decisions affecting other people does not mean you understand or relate to those other people. In fact, you very likely don’t. So you go out of your way to listen and empathize with others who have had different experiences than you, despite having the authority to make decisions for them granted to you by your GPA.

5. Convincing yourself and others to forgo instant gratification, often through strategic distraction.

Everyone knows the famous marshmallow test, where kids who could delay eating one marshmallow in exchange for two later on ended up better off in life. But the most important part of the test is often overlooked. The kids exercising patience often didn’t do it through sheer will. Most kids will take the first marshmallow if they sit there and stare at it. The patient ones delayed gratification by distracting themselves. They hid under a desk. Or sang a song. Or played with their shoes. Walter Mischel, the psychologist behind the famous test, later wrote:

The single most important correlate of delay time with youngsters was attention deployment, where the children focused their attention during the delay period: Those who attended to the rewards, thus activating the hot system more, tended to delay for a shorter time than those who focused their attention elsewhere, thus activating the cool system by distracting themselves from the hot spots.

Delayed gratification isn’t about surrounding yourself with temptations and hoping to say no to them. No one is good at that. The smart way to handle long-term thinking is enjoying what you’re doing day to day enough that the terminal rewards don’t constantly cross your mind.

In technology, the obvious revolutions often come last.

The internet was around for decades before it felt personal. It started in labs, crept into offices, and only later landed in our homes. The smartphone wasn’t just a new form of communication – it was the moment computing shifted from corporate IT departments to our front pockets.

AI is accelerating faster than any previous wave of technology. In less than five years, we’ve gone from jaw-dropping demos of GPT-3 to a reality where millions of people interact with AI every day (sometimes without realizing it). Most of the attention so far has focused on the technical layer: model performance, token pricing, enterprise use cases. But the most transformative changes are likely to happen at the level of interface, brand, and emotional resonance.

The tools that stick won’t just be the most accurate. They’ll be the most intuitive, the most culturally fluent, the ones that feel like they belong in your life without demanding to be learned. That’s where the real leverage lies, and where consumer AI is about to get very interesting.

Because something big is happening now. Token costs are falling (OpenAI has slashed prices by more than 90% since 2020) making it cheaper and more feasible for developers to build and ship consumer AI applications. Fine-tuning models is becoming easier. The technical moat (if there ever was one) is evaporating. And as infrastructure becomes cheaper and more accessible, AI’s next act is coming into focus: the consumer.

“What once felt modern now feels immovable. These bedrock apps ossified, and AI is revealing just how brittle they’ve become.”

Because consumers don’t care about your model size. They care whether it helps them get through the day with a little less friction.

Think about the tools we use every day: Gmail. iCalendar. Whatsapp. They were built for the web, optimized for mobile, and essentially left to rot. What once felt modern now feels immovable. These bedrock apps ossified, and AI is revealing just how brittle they’ve become. They weren’t designed for a world where your technology listens, adapts, and acts without instruction.

Consumer AI isn’t about chatbots. Not the way we’ve come to know them, anyway. It’s about escaping the tired web of buttons and dropdowns we’ve been clicking through for years. The real opportunity is interface: tools that don’t just respond to commands but anticipate context. It’s not just about better UX. It’s about a new class of interaction altogether.

This could mean a home-buying concierge that doesn’t just show you listings, but understands your daily commute, dog-walking routine, and what kind of light you like in the mornings. A personal finance system that syncs with your partner’s calendar and cash flow, so you plan together without talking about money every day. Or a piano coach that listens as you play and adjusts your practice routine in real time, because you finally have a teacher with infinite patience.

Chatbots might have kicked off the era of conversational AI, but the revolution is in what comes after: ambient, embedded, invisible tools that behave more like teammates than software.

“The winners will look less like OpenAI and more like Nike or Pixar: emotionally fluent, culturally embedded, behavior-shaping machines hiding in plain sight.”

Some of this is already happening. Well, sort of. Rewind.ai is giving users searchable memory across their digital lives. Rabbit’s R1 promises to remove the “app layer” entirely by turning natural language into actions. Humane’s Ai Pin, while flawed, is at least asking the right question: what does computing look like when you don’t have to look at a screen?

None of these products have nailed it. Most were met with bad reviews. Some feel like punchlines. But they’re reaching for something important. They’re trying to imagine a future where interface is no longer constrained by screens and keyboards. That matters. And while they’re clearly not the final form, they point toward a frontier we haven’t yet fully explored. These are the early missteps of a new genre; not failures of ambition, but signs that something new is struggling to be born.

History reminds us that form factor changes are rarely incremental. The PC didn’t lead to the smartphone – it required a complete reimagining of interface, distribution, and consumer behavior. We are due for another leap like that. Apple’s Vision Pro, Meta’s Ray-Ban smart glasses, and AI-driven wearables like the Oura Ring are early hints of what might come next.

Still, the path to mass adoption isn’t paved in code: it’s paved in trust, usability, and relevance. This is where many investors hesitate. Enterprise AI is easy to underwrite: there’s a sales pipeline, an efficiency metric, an ROI. Consumer AI feels squishier. It relies on taste. On cultural timing. On brand. It’s harder to spreadsheet.

But that’s what makes it so compelling.

“The best consumer AI product of the next five years won’t wow you with its intelligence. It’ll earn your trust. And never ask for your attention.”

Brand, after all, is a proxy for trust. And trust is the most valuable commodity in a world where AI agents will act on your behalf. Within five years, the most beloved AI product won’t have an app, a screen, or a UI, and its brand will be more trusted than your bank. Consumer AI isn’t a technical breakthrough; it’s a cultural one. The winners will look less like OpenAI and more like Nike or Pixar: emotionally fluent, culturally embedded, behavior-shaping machines hiding in plain sight. That’s where the defensibility lies – not in proprietary models, but in emotional resonance and behavioral lock-in. Just like Apple. Just like Spotify. Just like every consumer product that became infrastructure in disguise.

So where does this go?

In the next 18–24 months, most consumer AI experiments will flop. The hardware won’t work. The assistants will misfire. The reviews will be brutal. That’s fine. That’s how interface revolutions always begin; not with polish, but with friction. What matters is that a few teams will get it right. They’ll combine cultural intuition with technical leverage. They’ll design not for features, but for feelings. And when they launch, it won’t be clear whether they’re apps or brands or behaviors – only that they make life easier, more human, more yours. The best consumer AI product of the next five years won’t wow you with its intelligence. It’ll earn your trust. And never ask for your attention.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the MIT Media Lab, a place I helped create not to organize what was already known, but to make space for what wasn’t.

It was interdisciplinary before the word became decor. It was designed for people who didn’t fit into departments. In fact, many of its founding faculty were misfits in the most productive sense: outsiders in their own disciplines, a veritable Salon des Refusés. We weren’t solving problems. We were developing solutions without knowing the problems. That’s how breakthroughs happen, at the edges, where curiosity is free to wander and orthodoxy is politely ignored.

The Lab’s purpose then, as now, was to explore what computers might mean for everyday life. Not computing, but living. It was never only about technology. It was about perspective. As I’ve said before, the best vision is peripheral vision.

The same could be said of Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, and Bell Labs. These were not just institutions of instruction. They were catalysts that attracted visionaries and outsiders, bringing together brilliant minds who might otherwise never have collaborated. They treated form as a form of inquiry. They questioned the boundaries between disciplines and then blurred them deliberately. They approached taste as methodology. And they did it by creating space—not just physical space, but cultural permission—for experimentation without expectation.

Today, we find ourselves in a moment that requires a similar response.

AI is not simply a faster way to do what we’ve already done. It’s a medium shift, a new substrate for thought, interaction, and aesthetics. But instead of treating it that way, we’re drizzling it onto legacy systems in ways that feel fundamentally mismatched. A few assistants here, a couple auto-completes there. More productivity, less imagination.

What we need is not more apps. What we need are new models, ones that challenge assumptions rather than reinforce them.

The environments that foster true innovation combine friction between disciplines, treat computation as a raw material, and allow design to lead rather than lag. One such effort is unfolding in New York: AIR, short for AI Residency, a new kind of accelerator for design-led AI products. Founders are encouraged not to chase metrics, but to ask better questions. What does it feel like to use this? What kind of world does it assume? What kind of relationships does it create?

Too much of today’s AI conversation revolves around scale: How many users? How fast is the inference? How good is the ROI? These are fine questions, but they are not the interesting ones.

The interesting questions are more fundamental: What new literacies will we need? What new misuses will emerge? Can this technology help us understand ourselves better?

History tells us that significant ideas rarely come from the center. They begin at the margins, where ideas are allowed to be incomplete, even incorrect. Places where success is not the goal, but learning is.

Efforts like AIR matter because they create the conditions where breakthroughs tend to happen. The next big thing often starts as something strange. It does not arrive fully formed, or announce itself with clarity or consensus. It is shaped by small, curious groups, exploring the paths others have overlooked.

The Media Lab taught me that the future doesn’t start with a plan; it starts with an experiment. If history is any guide, the future of technology won’t be determined by incumbents or insiders. It will be authored by small groups with unusual perspectives and the freedom to follow them.

We should support that pursuit. We should build the spaces that make them possible.

Because what comes next is not a product. It is a provocation.

Which of my strongest beliefs are formed on second-hand information vs. first-hand experience?

If I could not compare myself to anyone else, how would I define a good life?

Whose views do I criticize that I would actually agree with if I lived in their shoes?

Who do I envy that is actually less happy than I am?

Looking back, am I any good at anticipating how I would feel and react to risks that actually occurred?

Is my desire for more money based on the false belief that it will solve personal problems that have nothing to do with money?

How many of my principles are cultural fads?

Whose silence do I mistake for agreement?

What kind of lifestyle would I live if no one other than my immediate family could see it?

What events nearly happened that would have fundamentally changed my life, for better or worse, had they occurred?

What views do I claim to believe in that I know are wrong but I say them because I don’t want to be criticized by my employer or industry?

How much of what I do is internal benchmark (makes me happy) vs. external benchmark (I think it changes what other people think of me)?

Am I thinking independently or going along with the tribal views of a group I want to be associated with?

Whose approval am I auditioning for?

Which of my principles would I abandon if they stopped earning me praise and recognition?

If I could see myself talk, what would I cringe at the most?

What question am I afraid to ask because I suspect I know the answer?

How much have things outside of my control contributed to things I take credit for?

How do I know if I’m being patient (a skill) or stubborn (a flaw)?

What crazy genius that I aspire to emulate is actually just crazy?

What strong belief do I hold that’s most likely to change?

Which future memory am I creating right now, and will I be proud to own it?

Am I addicted to cheap dopamine?

If I were on my deathbed tomorrow, what would I regret most?

We launched Collab+Sesame in 2016 as a pre-seed and seed-focused fund with a simple but powerful thesis: as tech entrepreneurs come of age, they would create a new wave of products and services to transform the kids’ space.

Sesame Street’s Endowment took a courageous step. It entrusted us with its brand, one of the best brands in the world, along with decades of research, a global audience, and a reputation built on kindness and learning, and said, “Show us what you can do.” We were humbled by that vote of confidence, and every day since, we’ve been mindful of the responsibility.

Fast-forward to present day, and here are the numbers through March 31, 2025:

- Net TVPI: 5.3x

- Net DPI: 2.6x

- Net IRR: 38.1%

These metrics rank in the top decile for Net DPI, Net TVPI, and Net IRR among all global venture capital funds in that vintage (PitchBook’s Q3 2024 benchmarks, with preliminary Q4 data).

But these returns are about more than just numbers. Along the way, we’ve been fortunate to back some incredible teams, including Lovevery, Outschool, Step, OK Play (acquired by Dapper Labs), Yup (acquired by Prenda), Luminopia, and others. Their hard work and vision have been instrumental in shaping this success.

Beyond financial returns, these numbers represent the foundation for new research and initiatives that reach millions of children worldwide. Every dollar we’ve returned to Sesame Street’s Endowment flows back into the mission that first inspired us: helping kids learn, empathize, and explore.

Collab+Sesame isn’t a story about charity, nor a conventional venture fund. It’s proof that when you blend rigorous investment discipline with a genuine mission, you can deliver market-leading returns and meaningful change.

Read our 2016 launch post and explore how Wired, TechCrunch, and The New Yorker covered the start of this journey.

Hat tip to Tim Brady and Geoff Ralston for creating ImagineK12, which was an early inspiration for Collab+Sesame.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. There can be no assurance that any Collaborative fund or investment will achieve its objective or avoid substantial losses. Certain statements contained herein reflect the subjective views and opinions of Collab. Such statements cannot be independently verified and are subject to change. In addition, there is no guarantee that all investments will exhibit characteristics that are consistent with the initiatives, standards, or metrics described herein. Certain portfolio companies shown herein are for illustrative purposes only and are a subset of Collaborative investments. Not all investments will have the same characteristics as the investments described herein. Certain of the investments made by Collab+Sesame and their performance are unrealized. Actual realized returns may different materially from the currently valued returns of these investments. References to “Net IRR” are to the internal rate of return calculated at the fund level. In addition, references to “Net IRR”, “Net TVPI” and “Net DPI” are calculated after payment of applicable management fees, carried interest and other applicable expenses. Internal rates of return are computed on a “dollar-weighted” basis, which takes into account the timing of cash flows, the amounts invested at any given time, and unrealized values as of the relevant valuation date.

It should not be assumed that any impact initiatives, standards or metrics described herein will apply to each asset in which any Collab fund invests or that they have applied each of the prior investments. Impact of an investment is only one of the many considerations that the Collab funds take into account when making investment decisions, and other considerations can be expected in certain circumstances to outweigh those considerations.

Thirty-seven thousand Americans died in car accidents in 1955, six times today’s rate adjusted for miles driven.

Ford began offering seat belts in every model that year. It was a $27 upgrade, equivalent to about $190 today. Research showed they reduced traffic fatalities by nearly 70%.

But only 2% of customers opted for the upgrade. Ninety-eight percent of buyers preferred to remain at the mercy of inertia.

Things eventually changed, but it took decades. Seatbelt usage was still under 15% in the early 1980s. It didn’t exceed 80% until the early 2000s – almost half a century after Ford offered them in all cars.

It’s easy to underestimate how social norms stall change, even when the change is an obvious improvement. One of the strongest forces in the world is the urge to keep doing things as you’ve always done them, because people don’t like to be told they’ve been doing things wrong. Change eventually comes, but agonizingly slower than you might assume.

Dunkirk was a miracle. More than 330,000 Allied soldiers, pinned down by Nazi attacks, were successfully evacuated from the beaches of France back to England, ferried by hundreds of small civilian boats.

London broke out in celebration when the mission was completed. Few were more relieved than Winston Churchill, who feared the imminent destruction of his army.

But Edmund Ironside, commander of British Home Forces, pointed out that if the Allies could quickly ferry a third of a million troops from France to England while avoiding aerial attack, the Germans probably could, too. Churchill had been holding onto hope that Germany couldn’t cross the Channel with an invasion force; such a daring mission seemed impossible. But then his own army proved it was quite possible. Dunkirk was both a success and a foreboding.

Your competitors can probably innovate and execute as well as you can. So every time you uncover a new talent you’re proud of, temper your thrill with the acceptance that other people who want to win as badly as you probably aren’t far behind.

Notorious BIG once casually mentioned that he began selling crack in fourth grade. He explained:

They [teachers] was always like, “Take the talent that you have and think of something that you can do in the future with it.”

And I was like, “Well, I like to draw.” So what could I do with drawing? What am I gonna be, an art dealer? I’m not gonna be that type. I was thinking maybe I can do big billboards and shit. Like commercial art.

And then after that I got introduced to crack. Haha, now I’m thinking, commercial art?! Haha. I’m out here for 20 minutes and I can make some real, real money, man.

Incentives drive everything, and most of us underestimate what we’d be willing to do if the incentives were right.

When Barack Obama discussed running for president in 2005, his friend George Haywood – an accomplished investor – gave him a warning: the housing market was about to collapse, and would take the economy down with it.

George told Obama how mortgage-backed securities worked, how they were being rated all wrong, how much risk was piling up, and how inevitable its collapse was. And it wasn’t just talk: George was short the mortgage market.

Home prices kept rising for two years. By 2007, when cracks began showing, Obama checked in with George. Surely his bet was now paying off?

Obama wrote in his memoir:

George told me that he had been forced to abandon his short position after taking heavy losses.

“I just don’t have enough cash to stay with the bet,” he said calmly enough, adding, “Apparently I’ve underestimated how willing people are to maintain a charade.”

Irrational trends rarely follow rational timelines. Unsustainable things can last longer than you think.

When the Black Death plague entered England in 1348, the Scots up north laughed at their good fortune. With the English crippled by disease, now was a perfect time for Scotland to stage an attack on its neighbor.

The Scots huddled together thousands of troops in preparation for battle. Which, of course, is the worst possible move during a pandemic.

“Before they could move, the savage mortality fell upon them too, scattering some in death and the rest in panic,” historian Barbara Tuchman writes in her book A Distant Mirror.

There’s a powerful urge to think risk is something that happens to other people. Other people get unlucky, other people make dumb decisions, other people get swayed by the seduction of greed and fear. But you? Me? No, never us. False confidence makes the eventual reality all the more shocking.

Some are more susceptible to risk than others, but no one is exempt from being humbled.

Dr. Dan Goodman once performed surgery on a middle-aged woman whose cataract had left her blind since childhood. The cataract was removed, leaving the woman with near-perfect vision. A miraculous success.

The patient returned for a checkup a few weeks later. The book Crashing Through writes:

Her reaction startled Goodman. She had been happy and content as a blind person. Now sighted, she became anxious and depressed. She told him that she had spent her adult life on welfare and had never worked, married, or ventured far from home – a small existence to which she had become comfortably accustomed. Now, however, government officials told her that she no longer qualified for disability, and they expected her to get a job. Society wanted her to function normally. It was, she told Goldman, too much to handle.

Every goal you dream about has a downside that’s easy to overlook.

Historian John Meecham writes:

When we condemn [the past] for slavery, or for Native American removal, or for denying women their full role in the life of the nation, we ought to pause and think: What injustices are we perpetuating even now that will one day face the harshest of verdicts by those who come after us?

This applies to so many things.

What is the modern version of cigarettes, which were doctor-recommended just a few generations ago? We didn’t know dinosaurs existed 200 years ago, which makes you wonder what else is out there that we’re oblivious to today. What company is the modern Enron, so obviously a fraud? What do most people – not a few wackos, but most of us – believe that will look something between hilarious and disgraceful 100 years from now?

A lot of history is just gawking at how wrong, how blind, people can be. Disastrously wrong, embarrassingly blind. Millions of people, all at the same time. When you then realize that today will be considered history in a few generations … oh dear. It’s unpleasant. But also fascinating.

Apollo 11 was the first time in history humans visited another celestial body.

You’d think that would be an overwhelming experience – literally the coolest thing any human had ever done. But as the spacecraft hovered over the moon, Michael Collins turned to Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin and said:

It’s amazing how quickly you adapt. It doesn’t seem weird at all to me to look out there and see the moon going by, you know?

Three months later, after Al Bean walked on the moon during Apollo 12, he turned to astronaut Pete Conrad and said “It’s kind of like the song: Is that all there is?” Conrad was relieved, because he secretly felt the same, describing his moonwalk as spectacular but not momentous.

Most mental upside comes from the thrill of anticipation – actual experiences tend to fall flat, and your mind quickly moves on to anticipating the next event. That’s how dopamine works.

If walking on the moon left astronauts underwhelmed, what does it say about our own earthly goals and expectations?

John Nash is one of the smartest mathematicians to ever live, winning the Nobel Prize. He was also schizophrenic, and spent most of his life convinced that aliens were sending him coded messages.

In her book A Beautiful Mind, Silvia Nasar recounts a conversation between Nash and Harvard professor George Mackey:

“How could you, a mathematician, a man devoted to reason and logical proof, how could you believe that extraterrestrials are sending you messages? How could you believe that you are being recruited by aliens from outer space to save the world?” Mackey asked.

“Because,” Nash said slowly in his soft, reasonable southern drawl, “the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously.”

This is a good example of a theory I have about very talented people: No one should be shocked when people who think about the world in unique ways you like also think about the world in unique ways you don’t like. Unique minds have to be accepted as a full package.

More:

Below is a transcript from a recent podcast I did on the tariff news.

My business that I use for my books and my speaking and whatnot is called Long Term Words, LLC. Now, the name of that is not very important. Nobody sees it unless I’m doing a talk with you or something. But let me tell you the origin behind that name, why I picked that name, because it’s relevant to today’s episode.

I’ve always wanted at least the opportunity that anything I write in a book or an article, that it has at least a fighting chance to still be relevant, 10, 20, even 50 years from now. I only want to write about things that are timeless because I’ve never enjoyed, as a reader, reading news that has an expiration date on it.

If this news article is not going to be relevant a year from now, it shouldn’t be relevant to me today. That’s always been my philosophy, and I’ve wanted to do that with my own writing. Write things that at least have a fighting chance for somebody to read and enjoy and maybe learn from many decades into the future.

That’s always been the goal. Long term words. I bring that up because today’s episode is going to be a rare departure from that in which I’m gonna talk about something that is happening in the news today and this week, and that is tariffs and the market reaction to it. We’ll get in that as well. So if that’s not your thing, if you’re only interested in the long term words, this episode might not be for you.

So before I jump into my detailed thoughts about what I think is going on, let me put my cards on the table. I think the tariffs are a terrible idea. Not just a terrible idea, but a horrendous idea.

Now I understand that all of us, everybody, including me, everybody can live in their own bubble. Particularly for these topics where it’s very hard to divorce economics and money from politics. So if you disagree with that broad view and you think the tariffs are a good idea, let me just state I respect you. I’d love to hear you. Everyone sees the world through their own unique lens, and it’s naive to assume that my lens is clearer than yours, even if it might be different.

Look, I’m a free market person. Of course. I understand the need for law and regulation and even tariffs in certain situations like masks during covid when we are reliant on other countries for things that we desperately needed, or military supplies, you don’t wanna re reliant on other countries making your military supplies in a war.

So tariffs can absolutely have their function in a well-run economy. But this what’s going on in the last week seems completely backwards, I think, to everything that we know and have learned about economics. Let me give you one analogy that’s been helpful to me with this. For nutrition science in terms of what kind of diet should you eat, what is the best diet that you and I can eat to live the healthiest life?

Nutritionists and health experts fiercely disagree on what the best diet you should eat. Should it be keto, should you be vegan? Everything in between. There’s so many different nuanced views over nutrition. But everybody agrees that eating lots of refined sugar is bad. There’s no disagreement about that. If you’re eating lots and lots of processed, refined sugar, that’s not good for you, even if there’s so much disagreement about everything else, and I think that is how economics works as well. There is so much disagreement. Among economists and politicians and investors over how to run the economy, what’s the right level of taxation?

Should it be more, should it be less? What’s the right level of regulation? Fierce disagreements among very smart people, but tariffs are the equivalent of refined sugar. You’ll be very hard pressed to find many economists. Of course, there’s always going to be one or two standouts here or there that make a lot of noise.

But one of the most agreed upon topics in economics is that tariffs are bad and trade wars are destructive. And the broad reason why is because tariffs by and large do two things. They raise prices for consumers and they make manufacturers back at home less competitive.

And one good way to explain this, I think that’s been helpful for my thinking, is just understanding the value of specialization of trade.

Now, I am a writer. I might have some skills at writing. I do not have any skills whatsoever at plumbing or electricity.

So when I need those things resolved, I hire a plumber, I hire an electrician because they are much better at those tasks than I am in that situation. When I hire a plumber, the plumber is not taking advantage of me. Even though I have a trade deficit with him, because he’s probably not buying my books, but I’m buying his services.

I have a trade deficit with the plumber. Nobody is being taken advantage of in that situation. He has a skill that I don’t, I can exchange my money for his skills. Everybody is better off. He’s better off. I’m better off.

Most people can understand that at the individual level. And that is also true at the economic level. There are some skills that the United States has that we are ridiculously good and talented at. There are other things that other nations are much better than us. And there’s no shame in that, just in the same way that I am not shamed at the fact that I’m not good at plumbing.

It is specialization of labor. So I think in the United States historically and today, we are extremely good, I think we are the best in the world at three things, entrepreneurship, service, and very high end manufacturing like planes and, and rockets. I think we are the best in the world at that, but just like the plumber is much better at other things than I am, there are things that other countries are way better than the United States at manufacturing a lot of certain goods, particularly mass goods, particularly lower end goods like clothing and shoes.

I spoke to A CEO last week, and he told me something that was helpful in my thinking here. He said, look, if you give instructions to Chinese workers and you say, here’s how to make this part, here’s step one, step two, step three, they are better than anyone in the world at making that part.

They can do it cheaper, faster, more efficiently, higher quality. But if you went to those Chinese workers and you said, please go design me a new part, they’re not that good at it. Americans are way better at that task than assembling that part, and that’s why the back of your iPhone says, designed in California, made in China.

That’s exactly what he was speaking to.

So look, my, my standard asterisk here, you might disagree with that. You might have different views. None of this is black and white, but the statements about it almost always are, which makes this a hard thing to talk about. So if you disagree with those views, lemme say it again. I respect you. I would listen to you. I’m just putting my cards on the table.

One big factor that I think gets lost here. And I’m gonna speak in a second why I think there is such a push among certain people for tariffs and why they think there is the need for them. I’m going to speak to that in a second, but one factor that I think is very lost here is that, yes, the United States has lost a lot of manufacturing employment over the last 50 years.

Of course, it absolutely has. And often when that is addressed, it is immediately jumped to, that’s because we ship those jobs overseas. The factories that used to be in Indiana and Tennessee and Mississippi, we shipped them to Mexico and Canada and China. There is some truth to that. Of course, indisputably. There is, I think, a bigger truth that gets lost, which is that where a lot of those jobs went was not necessarily to another country, it was to automation.

My favorite example of this, I wrote this 10 years ago, I had to go fish this up from an old article that I wrote is about a US steel factory in Gary, Indiana. In 1950, this individual factory produced 6 million tons of steel with 30,000 workers. In 2010 it produced seven and a half million tons of steel with 5,000 workers. So during this period, they increased the amount of steel that they were making, and they did it with 25,000 fewer workers. They went from 30,000 workers to 5,000. That story, I think, can be repeated across virtually everything that is made in the United States and around the world over the last 50 years.

Very interesting thing that I read the other day: China, the manufacturing powerhouse of the globe, has fewer manufacturing workers today than they did 10 years ago. They’re making more stuff than ever before. They’re building factories faster than ever before, and they have fewer people working in those factories because China, more than anybody else probably throughout history, is installing and using robots and automation in their manufacturing at a ferocious pace.

And so you can keep making more and more stuff but you need fewer and fewer people working on those assembly lines. That is often lost in the debate because if we were to bring back the manufacturing capacity to the United States, and that’s a separate debate, that’s a much longer debate, but let’s say that we do, it would not in any circumstances bring back the manufacturing jobs and the employment levels that we had in the 1950s. It’s a very different world today than it was back then. One way to get a very good view of this is to go onto YouTube and search for a video of Tesla factories. Because Tesla, very similar to China, is big on automation in its assembly and robots. And compare a modern Tesla factory to the 1950s Ford assembly line. It could not be more night and day, it could not be more different. The modern assembly line is robots and machines. Versus the assembly line back in the 1950s, which was biceps and backs and legs. That today has been replaced by automation.

One other example of this in the auto industry in 1990, not that long ago, the average American auto worker like working on an assembly line, their share of total auto production was about seven vehicles per year. So take the number of vehicles that were produced in the United States, divide that by the number of auto workers, and it was about seven.

The average worker was responsible for seven vehicles per year by 2023. Again, that’s just like one generation apart. Not even that much. The average auto worker in the United States was responsible for producing 33 vehicles per year. It went from seven to 33.

So we are, we are still producing a lot of cars in the United States. We still make a lot of vehicles here in the United States. It just does not require the amount of labor that it used to.

Just a few years ago, the economics journalist Neil Irwin wrote, “in the newest factories, one can look across an airplane hangar size floor, and see only a small handful of technicians staring at computer screens, monitoring the work of the machines. Workers lifting and pushing and riveting are nowhere to be seen.” And so I think that that is how manufacturing works today. It is very high output and low head count. At least much lower than it used to be.

So even as a US faces a manufacturing boom, which it has by the way in the last decade, easy to overlook, that manufacturing just can’t be expected to create the kind of employment that you saw many decades ago.

Okay, so that is a good leadway into another topic, which is about what the world was like during the golden ages of manufacturing that we remember, you know, the people who are working in the auto plants and the steel mills in the 1950s and the 1960s and through the 1970s, I think that is by and large the world that a lot of people want to go back to. Very understandable. I do not look down upon them for wanting to go back to that world in the slightest because it was a great world. It was amazing when there were tens of millions of manufacturing jobs in the industrial parts of the United States.

The people who did not go to college, or even people who did, could go get and earn good wages, that was great. It was a wonderful thing, but lemme tell you at least part of why it occurred at the time. At the end of World War II in 1945, Europe and Japan were decimated into rubble. Whereas the United States, of course, had all of its manufacturing capacity intact and had all these gis coming home.

There were 16 million GIs who came home in 1945 and had all this pent up demand to buy homes and washing machines and cars and all the new gadgets. And because Europe and Japan were in rubble, America, by and large had global manufacturing to itself. It had like a monopoly on global manufacturing at the time because Europe and Japan was still trying to build themselves back from the devastation of the war.

China at this period was still kind of an economic backwater, wasn’t really part of the equation. It was also trying to recover from the ravages of World War II. Places like India and Bangladesh and Thailand that manufacture a lot today weren’t really part of the global manufacturing equation back then.

There was this period when, because of the state of global geopolitics, America had a manufacturing dominance to itself for a good 20 years from probably 1945 through the end of the 1960s. That was also a period when, for many different factors, we don’t need to go into all of them, but white collar workers were not making that much money.

If you worked on Wall Street in the 1970s, that was not a place to make a lot of money. That was an admin accounting job that was not very looked highly upon because you didn’t make that much money. Bankers were not making nearly the kind of money that they made in the decades before or after. This period, and that was important because the blue collar manufacturing workers, by comparison to others in the economy, to others in their town, were doing great.

So even if their wages were lower back then than they would be today, even adjusted for inflation, when the manufacturing worker compared themself to the banker or the accountant, or the lawyer or the doctor, by comparison, he said, I’m doing pretty great. I’m doing pretty well. And then two things happened starting around the 1970s that really accelerated in the eighties and nineties, which was one Japan and Europe kind of after having recovered from the ravages of World War II became manufacturing powerhouses in their own right.

One of the first signs of this was when Honda, Nissan and Toyota started selling cars in the United States, and people realized in the US that, Hey, actually. These are pretty good cars. These aren’t bad. It was easy to look down upon ‘em at first because they were small and had tiny little engines relative to the Chevy Camaro or the, the T-Bird, but this came during a period in the seventies and eighties when gas prices surged and all of a sudden those tiny little engines in a Honda Civic or a Toyota Corolla we’re what people wanted. And then all of a sudden, out of the blue, you went from incredible American dominance in car manufacturing from gm, Ford, and Chrysler to Honda, Toyota, and Nissan actually taking a lot of market share.

There’s a very good book I read a couple months ago. It’s called The Reckoning, and it’s about Ford’s decline and Nissan’s rise during this period, from the 1950s to the 1990s. And a lot of what happened to, to state it very generally, it’s more complicated than this, was companies like Ford, a GM in Chrysler, had so much dominance during this period, fifties, sixties, seventies, that when they started facing competition from foreign imports in the eighties and nineties, they kind of lost their way. They had such a stranglehold monopoly on auto manufacturing that they became much less competitive. And as I said earlier, that is one function that tariffs implement is when you don’t have to compete with foreign suppliers.

You become much less competitive. You become kind of fat and happy and lazy. In a way, and that was kind of the, the broad thesis of this book was that Ford became fat, happy, and lazy while Nissan and other Japanese auto manufacturers were just surging.

And so the manufacturing dominance, not just in autos but in lots of things, heavy machinery and whatnot, started to erode in the seventies, eighties, and nineties, and really started to explode higher in the two thousands when China really came on board in terms of global manufacturing. And that occurred at the same moment when white collar workers.

And finance and accounting and office jobs started making fortunes huge sums of money. So now at the same moment that the manufacturing worker was losing their jobs both to automation and foreign competition, the white collar workers were, were just having a field day and making money hand over fist, which made what manufacturing jobs existed feel even worse by comparison because let’s say you’re an auto worker making $25 an hour in one era, that might feel great, but if all of a sudden your neighbor who is a project manager at KPMG is making 300 grand a year, your $25 an hour doesn’t feel that great anymore. ‘cause your neighbor has, has a bigger house and more cars and is sending their kids to private school.

So by comparison, you feel worse off even if your wages adjusted for inflation may have been going up. And so you put all of that together. That is a very. Shorthand history. Of course, there are a billion variables that I left out in there, but I think that shorthand history is in broad strokes what has happened over the last 80 years.

It is so understandable that you have millions of workers who say, this economy worked for me 50 years ago and it doesn’t today. My dad, my grandpa had great jobs in the GM factory and I can’t have that today. So understandable that that would be the thought process of millions of workers, and I think it is naive and insulting for people who are on my side of the tariff debate who say tariffs are a bad idea who cannot understand the views of those kind of people. Because if I was in that situation, and if lots of people who disagree with tariffs were in that situation, they’d be arguing for the same thing.

I think one of America’s strengths over time, this has been true for hundreds of years, is this sounds kind of crazy, but I think it’s true. A firm belief in things that are probably not true. That has always been a strength of the United States. This goes back to the very early days of the settlers and the colonizers, whom back in Europe were told that America was a land of absolute abundance.

And when you got there, there would be just, you know, rivers overflowing with gold and whatnot. And actually it was like a malaria swap when they got to the East coast of the United States. But we believed it was always believed that this was the promise land. That was what brought the people over. And even when they came to the United States and settled. It was that belief too. America has always been so unbelievably optimistic, particularly at the individual level, and that’s why I think we’re so good at entrepreneurship. It’s this idea that you, the entrepreneur, even if you start as a, nobody can make it to become the next Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison. You can make it. You can do it. Not a lot of other cultures have that level of even like optimistic ignorance, because in many ways that’s what it is. But what that’s done is it’s created this incredible entrepreneurial society that has given us and the world some incredible world changing innovations in companies over the years.

And when I pair that belief with the observation that there are tens of millions of Americans who feel like the world doesn’t work for them anymore, who feels like this economy is not working for them anymore. That worries me. It worries me that a meaningful chunk of society does not have that optimistic ignorance. I mean that in a positive sense to think that, hey, the world is my oyster. The sky is the limit. I can go do it now. We’ve been through similar periods in the past, the 1930s, the 1970s, and we recovered from those. We recovered from those malaise periods, and I’m optimistic that we’ll recover from it this time, but we should not lose track of the fact that we are in one of those periods again.

Where this goes next, my guess is as good as yours. And both of our guesses are useless beacuse I don’t think anyone knows what’s gonna happen next. Interestingly, many of you will listen to this podcast the day that I publish it, which I guess is April 8th. Some of you will listen to it weeks in the future when half of what I just said will be outdated because the situation is changing so quickly.

That gets back to why I only want to do long-term words and why this is so against what I normally do. But let me say a couple of things about. Investing because that has been the initial reaction to the tariffs has been entirely in the stock market, which as I speak here, is down about 20% or so from its highs that were reached just a couple weeks ago.

Now, the tariff impact has not hit the broader economy in terms of inflation at the grocery store or mass layoffs or whatnot. But so far it’s been in the stock market. So even if that is a very minor part of what will impact the economy, let me speak to that just a bit. I, of course have, have been glued to Twitter over the last week just trying to understand what’s happening and hear other people’s views.

I’ve watched it with a sense of shock and just confusion trying to piece together what’s happened, but it has not in the slightest changed how I invest, and I extremely doubt that it ever will. I think it is possible to be an engaged and informed citizen, even a social media junkie reading the news and a calm investor at the same time.

I purchased stocks early last week, not because of anything that was going on in the news, but because you gotta do that every month around the first of the month. I do it every single month. I’ve done that for, uh, I don’t know, 20 years now. I’ll do it next month. I’ll do it the month after that. That won’t change. I think it, it never changes. So I think you can simultaneously dollar cost average. Remain long-term, optimistic, not panic about anything that’s going on in the world. You can enjoy life, spend time outdoors, hang out with your kids, eat good food, listen to good music, have a good time, and at the same time, if you are of the same belief of me, realize how destructive and unnecessary what we’re going through is.

You can do all of that at the same time. It’s not like you have to be optimistic or pessimistic. I am very optimistic on the long term, even if I think this is a bad idea, that’s not a contradiction. Something else I’ve been thinking about is that we have in the past been through much more uncertain times than we’re going through right now, but it never feels that way, or it rarely feels that way because when we think about the past economic crises, COVID, Lehman Brothers, 9/11, Pearl Harbor, those kind of events. We know how the story ended and we know that the story did end and we know that we eventually recovered. But whenever it is a current crisis, a current period of uncertainty, you don’t know that. You don’t know when it’s going to end. You don’t know how it’s gonna end, and some people don’t know if it will ever end.

And because of that, even if, I think without a doubt what we’re going through is less uncertain, less serious than other periods of economic upheaval. It rarely feels that way because we don’t know what’s gonna happen next. So every crisis has its own little unique flavor of what’s going on. But the common denominator is this feeling that you can’t see the future anymore. And that makes people go crazy in, turns them into political junkies. It makes ‘em make bad investing decisions. That’s always been the case. Try to avoid that. I would also say that for most investors, 99% of good investing is doing nothing.