The Atlantic - Technology

The Atlantic's technology section provides deep insights into the tech giants, social media trends, and the digital culture shaping our world.

It’s a rare thing to shoot yourself in the foot and win a marathon. For years, Elon Musk has managed to do something like that with Tesla, achieving monumental success in spite of a series of self-inflicted disasters. There was the time he heavily promoted the company’s automated factory, only to later admit that its “crazy, complex network of conveyor belts” had thrown production of the Model 3 off track; and the time a tweet led him to be sued for fraud by the Securities and Exchange Commission; and the time he said that the Tesla team had “dug our own grave” with the massively delayed and overhyped Cybertruck. Tesla is nonetheless the most valuable car company in the world by a wide margin.

But luck runs out. Yesterday evening, Tesla reported first-quarter earnings for 2025, and they were abysmal: Profits dropped 71 percent from the same time last year. Musk sounded bitter on the call with investors that followed, blaming the company’s misfortune on protesters who have raged at Tesla dealerships around the world over his role running DOGE and his ardent support of far-right politicians. “The protests that you’ll see out there, they’re very organized. They’re paid for,” he said, without evidence.

Then he pivoted. Although Musk described DOGE as “critical work,” he said that his “time allocation” there “will drop significantly” next month, down to just one or two days a week. He’s taking a big step back from politics and returning the bulk of his attention to Tesla, as even his most enthusiastic supporters have begged him to do. (Tesla did not immediately return a request for comment.)

One bad quarter won’t doom Tesla, but it’s unclear how, exactly, the company can move forward from here. Arguably, its biggest and most immediate problem is that electric-vehicle fans in America, who tend to lean left politically, do not want to buy Musk’s cars anymore. The so-called Tesla Takedown protests have given people who feel helpless and angry about President Donald Trump’s policies a tangible place to direct their anger. Because Musk was also the Trump campaign’s biggest financier, those protesters saw a Tesla boycott as one of the best ways to hit back. The fact that these demonstrations were the first thing Musk brought up on the earnings call speaks volumes about how rattled he must be; Tesla purchases have been down considerably this year in the U.S., even as EV sales keep rising.

And while some people in Europe may believe they do not have much cause to care about DOGE, they do care that Musk has been promoting far-right political actors, most notably Germany’s Alternative for Germany party. That seems to be having a palpable impact on Tesla’s sales; they’ve been tanking by double-digits across Europe.

Buyers are turning to other car brands for their electric-powered driving needs, and those brands are happy to take their business. Tesla may have effectively created the modern EV sector, but the competition is catching up. In the U.S. alone, several car companies now offer electric options with more range, better features, and lower prices than Tesla. A long-awaited cheaper new Tesla could bring in more buyers, but there’s been little fanfare around it, perhaps because Musk is preoccupied with autonomous taxis and self-driving cars; a new “robotaxi” service is supposedly launching in June, in Austin. Yet any self-driving-technology investment depends on Tesla’s ability to sell cars right now to finance those dreams, and that’s where Tesla is likely to continue to have trouble.

[Read: The great Tesla sell-off]

Finally, there’s the bigger problem of China. Musk’s company effectively showed that country how to make modern EVs, and although Teslas still sell well enough there, Musk is up against dozens of new Tesla-like companies that have taken his ideas and run wild. Electric cars in China can be had with more advanced features than what Tesla offers, faster charging times, and more advanced approaches to automated driving. (Case in point: I am writing this story in Shanghai, from the passenger’s seat of an EV that can swap its depleted battery for a fresh one in mere minutes.)

At most companies, it’d be long past time to show the CEO the door. But Tesla’s stock price is inextricably linked to Musk and his onetime image as Silicon Valley’s greatest living genius. Even if Musk were to move on, it’s unclear whether Tesla as a brand could recover, Robby DeGraff, an analyst at the research firm AutoPacific, told me. “I’m genuinely not convinced removing him would be enough,” DeGraff said. “I do believe the potential is there for the brand to steer itself around with exciting, quality, innovative products. But there’s a colossal amount of repair work that needs to be done behind the scenes first.”

Unfortunately for Tesla, the great disruptor of the automotive industry is beginning to feel a lot like a “legacy” car company, struggling to figure out what’s next and getting lapped by newcomers. The competition has the advantage of not being inextricably tied to a boss who’s made the brand so toxic that people would rather go to his dealerships to wave angry signs than to buy cars. If Tesla’s future rests on left-leaning EV fans forgiving Musk for backing Trump, boosting the AfD party in Germany, and gleefully putting hundreds of thousands of federal employees out of work, then Musk may find himself longing for the days when his biggest problem was building a wild-looking stainless-steel truck.

Updated at 10:26 a.m. ET on April 23, 2025

Everywhere I look on social media, disembodied heads float in front of legal documents, narrating them line by line. Sometimes they linger on a specific sentence. Mostly they just read and read.

One content creator, who posts videos under the username I’m Not a Lawyer But, recently made a seven-minute TikTok in which she highlighted the important sentences from Drake’s 81-page defamation complaint against Universal Music Group. Another described herself in a recent video as “literally reading through the receipts of Justin Baldoni’s 179-page lawsuit,” referring to one stage of a complicated legal battle between Baldoni and his It Ends With Us co-star, Blake Lively, which is the hot legal case of the moment. The threads of this conflict are too knotted for me to fully untangle here, but the dispute began in December with Lively accusing Baldoni of inappropriate on-set behavior and of a secret social-media campaign against her. It became chaotic—and ripe for play-by-play commentary—in February when Baldoni, who has denied Lively’s allegations, launched a website with the URL thelawsuit.info to tell his side of the story.

The creators I’m seeing have loyal, long-term audiences and sell T-shirts and water bottles emblazoned with obscure references. They go by names such as Lawyer You Know and Legal Bytes (“Explaining the law one bite at a time!”) and sometimes appeal to expertise, usually by proving that they are actual attorneys. For some, though, their bona fides are looser: “I’m not an attorney, but I was raised by attorneys,” one creator said in a recent video.

The popularity of this material—a kind of lawyerly ASMR—has surprised even some of the people who make it. “It seems odd to us,” Stewart Albertson, one half of the podcast Ask 2 Lawyers, told me. He and his co-host, Keith Davidson, in fact are lawyers, and sometimes get 100,000 views on lengthy videos in which they go through a legal motion line by line. They’ve asked the audience if they should go faster and skip over some things. The commenters say no. They love monotony and minutiae. “People talk about, ‘Oh, I could go to sleep to these guys,’” Albertson told me. These are words of affection. He and Davidson know that because the commenters have also asked them to make Ask 2 Lawyers merch (specifically, they would like coffee mugs that say “12(b)(6)” on them, in reference to a type of legal motion filed by Blake Lively).

Albertson and Davidson spent more than a decade making marketing videos explaining trust and estate law, their firm’s speciality. Now they mostly make what they call educational content in which they explain high-profile legal disputes. They started with a series on a dramatic saga involving Tom Girardi, the ex of one of the women on Bravo’s Real Housewives of Beverly Hills. (Girardi was famous for his heroism in the Erin Brockovich case; he is now infamous for having been convicted of embezzlement and wire fraud, as well as for the way his criminal activity affected the fascinating women of RHOBH.) Although the topics are salacious, the two lawyers’ videos are, with all due respect, breathtakingly boring. “You know, we’re kind of bringing calm to chaos,” Albertson said. “Maybe that’s what speaks to people.”

[Read: What the JFK file dump actually revealed]

That’s part of it, but it’s also the simple allure of stacks of papers. Markos Bitsakakis, a 25-year-old TikTok creator from Toronto who also runs an herbal-honey company, sometimes gets 1 million likes on a video in which he flips through huge dossiers the entire time he is talking. (He has so far published 12 installments of a series titled “The Downfall of Blake Lively & Ryan Reynolds.”) He’ll explain to the viewers that he’s just spent nine hours with one document, or that he’s recording at two in the morning because he has been reading for so long. His followers joke that a printer must, as the saying goes, hate to see him coming. “I have like a million files,” he told me. “Mentally, I’m 45 years old,” he added, to explain why he prefers hard copies to PDFs. The way that he dramatizes his work situates him in an online tradition of romanticizing studying and research (especially when they’re done alone). “Lucky for you guys I never travel anywhere without my files,” he said at the start of a video he recorded while on a trip.

Celebrity lawsuits have always been followed in detail by tabloids and gossip bloggers, and our reality-TV culture has been fascinated for some time with the idea of “receipts”—proof of malfeasance, often in the form of text messages or screenshots. But this is newer. Amateur legal analysis is now a whole category of content creation, and thick, formal documents are the influencers’ bread and butter.

These creators often present a very internet-age populist message alongside their analysis—many of the videos allow for the possibility that anyone can become an expert simply by having the commitment to read and keep reading the things that they are able to access freely online. Another of their stated commitments is to the notion of transparency, which helps explain why many of the same creators have expressed an interest in the National Archives’ recent dump of files pertaining to the John F. Kennedy assassination. Of course, some of the draw is gossip. But to a significant degree, I think the draw really is files.

Files are never-ending stories—or at least they can feel that way when a case drags on, providing a new flurry of paperwork week after week. Katy Hoffman, a 32-year-old in Kansas City, follows CourtListener and PacerMonitor for updates on the Baldoni-Lively case and told me that this is effectively her unwinding ritual. Instead of watching TV or scrolling Instagram at night, she’ll read whatever is new. “I try to maintain a good balance,” she said. That last hour of the day that everyone spends doing something pointless is the one she spends on this, she told me. (She also makes her own videos sometimes, though her audience is quite small.)

Similarly, Julie Urquhart, a 49-year-old teacher from New Brunswick, Canada, told me that she spends much of her free time reading court documents and then making short TikTok videos about them. “I’ve read everything you can on this case,” she told me. “All the lawsuits, multiple times.” She loved working at a radio station in college, so this is a hobby that can satisfy the same impulse to research and then broadcast, even if to a tiny audience. As with many other creators, Urquhart has recently focused on the Baldoni lawsuit, and it has caused her some grief: She takes Lively’s side, which she says has made her videos less popular and led people to be furious with her in the comments.

Here is where content about files becomes less fun. Particularly if you look at the comment sections, you’ll see a lot of vitriol against Lively—visible in much the same way as was vitriol against Amber Heard during the Johnny Depp trial or Evan Rachel Wood during her dispute with Marilyn Manson. Most of the creators I spoke with insisted that misogyny is not a factor in the success of their videos or in their own presentation of the facts, but this is not totally convincing. In 2020, I wrote about the rise of conspiracy theories about celebrities allegedly faking their pregnancies, which were transparently the product of resentment toward famous people and other elites, women especially, and I see quite a bit of that here as well. Commenters often express that they are tired of being “manipulated” by such people.

[Read: How a fake baby is born]

This is not to say that content about the Baldoni-Lively case is inherently toxic. In fact, it’s likely that these lawsuit influencers have had success with it because it’s fairly middle-of-the-road: mysterious, but not acutely morbid or upsetting like true crime can be. As Bitsakakis put it, the topic is “dramatic and exciting and salacious, but it isn’t necessarily as serious as nuclear war.” He thinks that he’s been rewarded by the TikTok algorithm for hitting that sweet spot. There are other legal topics he’d like to “investigate,” such as the Luigi Mangione case and the Sean “Diddy” Combs allegations, but those things may be just a little too dark to be pushed out into the main feed by the powerful recommendation engine. (For the same reason, many TikTok creators reference Blake Lively’s claims by saying “SH” rather than “sexual harassment.”)

The broad interest in this case—and its many files—has made for some strange bedfellows. Recently, New York magazine published a story on self-described liberals winding up on the YouTube page of the right-wing influencer Candace Owens, who dabbles in conspiracy theories and is currently working on a YouTube series trying to prove that Brigitte Macron was born a man, because they’re impressed by her ample Baldoni-Lively coverage. Owens is explicitly anti-#MeToo and sells Anti-Feminist baseball caps in her merch store, but viewers who don’t share her politics reportedly still enjoy watching her go through lots of legal documents and show her work. “I read them myself,” she told me. “I sit down with a pen, mark things up, use stickies, little different-colored stickies if I have questions, like for my lawyer, and he’ll explain things to me.”

These videos, as well as ones in which Owens speculates about whether Ryan Reynolds is gay, get millions of views. When I told her that I found it odd that so many people were interested in what amounted to a workplace dispute, she rejected the characterization. It was bigger than that, because it represented a shift in the way that people consume information, she told me. They’re more trusting now of online content creators who will present everything—all of the documents—than they are of traditional journalists, whom they perceive as being inappropriately possessive and aloof. “I’m very excited to see that both the left and the right are agreeing, finally, that we should really be removing a lot of the authority that we gave to the mainstream media to tell us what to think about other people,” she said. “I think it’s great. I think it’s brilliant.”

This was a sentiment I heard frequently from creators and saw often in the comments on their videos—people expressed a vaguely paranoid feeling that raw information is being deliberately kept away from them by reporters who hoard or hide it so that they can maintain their own power. It’s not an accurate understanding of the current state of journalism, but it is a popular one, and it helps explain the allure of reams of court documents. Davidson told me that the audience for Ask 2 Lawyers appreciates the granular level of detail that he and Albertson provide because it indicates that they are intelligent and curious enough to understand.

“We don’t talk down to them,” he said. “We don’t try to make them feel like, We know and you don’t. We’re here to give you the information, and you make up your own mind on it.” Clearly, people are really, really into that.

This article previously referred to Tom Girardi as the ex-husband of a cast member on The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills. The two are separated but not divorced.

There are really two OpenAIs. One is the creator of world-bending machines—the start-up that unleashed ChatGPT and in turn the generative-AI boom, surging toward an unrecognizable future with the rest of the tech industry in tow. This is the OpenAI that promises to eventually bring about “superintelligent” programs that exceed humanity’s capabilities.

The other OpenAI is simply a business. This is the company that is reportedly working on a social network and considering an expansion into hardware; it is the company that offers user-experience updates to ChatGPT, such as an “image library” feature announced last week and the new ability to “reference” past chats to provide personalized responses. You could think of this OpenAI as yet another tech company following in the footsteps of Meta, Apple, and Google—eager not just to inspire users with new discoveries, but to keep them locked into a lineup of endlessly iterating products.

The most powerful tech companies succeed not simply by the virtues of their individual software and gadgets, but by building ecosystems of connected services. Having an iPhone and a MacBook makes it very convenient to use iCloud storage and iMessage and Apple Pay, and very annoying if a family member has a Samsung smartphone or if you ever decide to switch to a Windows PC. Google Search, Drive, Chrome, and Android devices form a similar walled garden, so much so that federal attorneys have asked a court to force the company to sell Chrome as a remedy to an antitrust violation. But compared with computers or even web browsers, chatbots are very easy to switch among—just open a new tab and type in a different URL. That makes the challenge somewhat greater for AI start-ups. Google and Apple already have product ecosystems to slide AI into; OpenAI does not.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman recently claimed that his company’s products have some 800 million weekly users—approximately a tenth of the world’s population. But even if OpenAI had only half that number of users, that would be a lot of people to risk losing to Anthropic, Google, and the unending torrent of new AI start-ups. As other tech companies have demonstrated, collecting data from users—images, conversations, purchases, friendships—and building products around that information is a good way to keep them locked in. Even if a competing chatbot is “smarter,” the ability to draw on previous conversations could make parting ways with ChatGPT much harder. This also helps explain why OpenAI is giving college students two months of free access to a premium tier of ChatGPT, seeding the ground for long-term loyalty. (This follows a familiar pattern for tech companies: Hulu used to be free, Gmail used to regularly increase its free storage, and eons ago, YouTube didn’t serve ads.) Notably, OpenAI has recently hired executives from Meta, Twitter, Uber, and NextDoor to advance its commercial operations.

OpenAI’s two identities—groundbreaking AI lab and archetypal tech firm—do not necessarily conflict. The company has said that commercialization benefits AI development, and that offering AI models as consumer products is an important way to get people accustomed to the technology, test its limitations in the real world, and encourage deliberation over how it should and shouldn’t be used. Presenting AI in an intuitive, conversational form, rather than promoting a major leap in an algorithm’s “intelligence” or capabilities, is precisely what made ChatGPT a hit. If the idea is to make AI that “benefits all of humanity,” as OpenAI professes in its charter, then sharing these purported benefits now both makes sense and creates an economic incentive to train better and more reliable AI models. Increased revenue, in turn, can sustain the development of those future, improved models.

Then again, OpenAI has gradually transitioned from a nonprofit to a more and more profit-oriented corporate structure: Using generative-AI technology to magically discover new drugs is a nice idea, but eventually the company will need to start making money from everyday users to keep the lights on. (OpenAI lost well over $1 billion last year.) A spokesperson for OpenAI, which has a corporate partnership with The Atlantic, wrote over email that “competition is good for users and US innovation. Anyone can use ChatGPT from any browser,” and that “developers remain free to switch to competing models whenever they choose.”

[Read: The Gen Z lifestyle subsidy]

Anthropic and Meta have both taken alternative approaches to bringing their models to internet users. The former recently offered the ability to integrate its chatbot Claude into Gmail, Google Docs, and Google Calendar—gaining a foothold in an existing tech ecosystem rather than building anew. (OpenAI seemed to be testing this strategy last year by partnering with Apple to incorporate ChatGPT directly into Apple Intelligence, but this requires a bit of setup on the user’s part—and Apple’s AI efforts have been broadly perceived as disappointing.) Meta, meanwhile, has made its Llama AI models free to download and modify—angling to make Llama a standard for software engineers. Altman has said OpenAI will release a similarly open model later this year; apparently the start-up wants to both wall off its garden and make its AI models the foundation for everyone else, too.

From this vantage, generative AI appears less revolutionary and more like all the previous websites, platforms, and gadgets fighting to grab your attention and never let it go. The mountains of data collected through chatbot interactions may fuel more personalized and precisely targeted services and advertisements. Dependence on smartphones and smartwatches could breed dependence on AI, and vice versa. And there is other shared DNA. Social-media platforms relied on poorly compensated content-moderation work to screen out harmful and abusive posts, exposing workers to horrendous media in order for the products to be palatable to the widest audience possible. OpenAI and other AI companies have relied on the same type of labor to develop their training data sets. Should OpenAI really launch a social-media website or hardware device, this lineage will become explicit. That there are two OpenAIs is now clear. But it remains uncertain which is the alter ego.

Finals season looks different this year. Across college campuses, students are slogging their way through exams with all-nighters and lots of caffeine, just as they always have. But they’re also getting more help from AI than ever before. Through the end of May, OpenAI is offering students two months of free access to ChatGPT Plus, which normally costs $20 a month. It’s a compelling deal for students who want help cramming—or cheating—their way through finals: Rather than firing up the free version of ChatGPT to outsource essay writing or work through a practice chemistry exam, students are now able to access the company’s most advanced models, as well as its “deep research” tool, which can quickly synthesize hundreds of digital sources into analytical reports.

The OpenAI deal is just one of many such AI promotions going around campuses. In recent months, Anthropic, xAI, Google, and Perplexity have also offered students free or significantly discounted versions of their paid chatbots. Some of the campaigns aren’t exactly subtle: “Good luck with finals,” an xAI employee recently wrote alongside details about the company’s deal. Even before the current wave of promotions, college students had established themselves as AI’s power users. “More than any other use case, more than any other kind of user, college-aged young adults in the US are embracing ChatGPT,” the vice president of education at OpenAI noted in a February report. Gen Z is using the technology to help with more than schoolwork; some people are integrating AI into their lives in more fundamental ways: creating personalized workout plans, generating grocery lists, and asking chatbots for romantic advice.

AI companies’ giveaways are helping further woo these young users, who are unlikely to shell out hundreds of dollars a year to test out the most advanced AI products. Maybe all of this sounds familiar. It’s reminiscent of the 2010s, when a generation of start-ups fought to win users over by offering cheap access to their services. These companies especially targeted young, well-to-do, urban Millennials. For suspiciously low prices, you could start your day with pilates booked via ClassPass, order lunch with DoorDash, and Lyft to meet your friend for happy hour across town. (On Uber, for instance, prices nearly doubled from 2018 to 2021, according to one analysis). These companies, alongside countless others, created what came to be known as the “Millennial lifestyle subsidy.” Now something similar is playing out with AI. Call it the Gen Z lifestyle subsidy. Instead of cheap Ubers and subsidized pizza delivery, today’s college students get free SuperGrok.

AI companies are going to great lengths to chase students. Anthropic, for example, recently started a “campus ambassadors” program to help boost interest; an early promotion offered students at select schools a year’s worth of access to a premium version of Claude, Anthropic’s AI assistant, for only $1 a month. One ambassador, Josefina Albert, a current senior at the University of Washington, told me that she shared the deal with her classmates, and even reached out to professors to see if they might be willing to promote the offer in their classes. “Most were pretty hesitant,” she told me, “which is understandable.”

The current discounts come at a cost. There are roughly 20 million postsecondary students in the U.S. Say just 1 percent of them take advantage of free ChatGPT Plus for the next two months. The start-up would effectively be giving a handout to students that is worth some $8 million. In Silicon Valley, $8 million is a rounding error. But many students are likely taking advantage of multiple such deals all at once. And, more to the point, AI companies are footing the bill for more than just college students. All of the major AI companies offer free versions of their products despite the fact that the technology itself isn’t free. Every time you type a message into a chatbot, someone somewhere is paying for the cost of processing and generating a response. These costs add up: OpenAI has more than half a billion weekly users, and only a fraction of them are paid subscribers. Just last week, Sam Altman, the start-up’s CEO, suggested that his company spends tens of millions of dollars processing “please” and “thank you” messages from users. Tack on the cost of training these models, which could be as much as $1 billion for the most advanced versions, and the price tag becomes even more substantial. (The Atlantic recently entered into a corporate partnership with OpenAI.)

These costs matter because, despite AI start-ups’ enormous valuations (OpenAI was just valued at $300 billion), they are wildly unprofitable. In January, Altman said that OpenAI was actually losing money on its $200-a-month “Pro” subscription. This year, the company is reportedly projected to burn nearly $7 billion; in a few years, that number could grow to as much as $20 billion. Normally, losing so much money is not a good business model. But OpenAI and its competitors are able to focus on acquiring new users because they have raised unprecedented sums from investors. As my colleague Matteo Wong explained last summer, Silicon Valley has undertaken a trillion-dollar leap of faith, on track to spend more on AI than what NASA spent on the Apollo space missions, with the hope that eventually the investments will pay off.

The Millennial lifestyle subsidy was also fueled by extreme amounts of cash. Ride-hailing businesses such as Uber and Lyft scooped up customers even as they famously bled money for years. At one point in 2015, Uber was offering carpool rides anywhere in San Francisco for just $5 while simultaneously burning $1 million a week. At times, the economics were shockingly flimsy. In 2019, the owner of a Kansas-based pizzeria noticed that his restaurant had been added to DoorDash without his doing. Stranger still, a pizza he sold for $24 was priced at $16 on DoorDash, yet the company was paying him the full price. In its quest for growth, the food-delivery start-up had reportedly scraped his restaurant’s menu, slapped it on their app, and was offering his pie at heavy discount. (Naturally, the pizzeria owner started ordering his own pizzas through DoorDash—at a profit.)

These deals didn’t last forever, and neither can free AI. The Millennial lifestyle subsidy eventually came crashing down as the cheap money dried up. Investors that had for so long allowed these start-ups to offer services at artificially deflated prices wanted returns. So companies were forced to raise prices, and not all of them survived.

If they want to succeed, AI companies will also eventually have to deliver profits to their investors. Over time, the underlying technology will get cheaper: Despite companies’ growing bills, technical improvements are already increasing efficiency and driving down certain expenses. Start-ups could also raise revenue through ultra-premium enterprise offerings. OpenAI is reportedly considering selling “PhD-level research agents” at $20,000 a month. But it’s unlikely that companies such as OpenAI will allow hundreds of millions of free users to coast along indefinitely. Perhaps that’s why the start-up is currently working on both search and social media; Silicon Valley has spent the past two decades essentially perfecting the business models for both.

Today’s giveaways put OpenAI and companies like it only further in the red for now, but maybe not in the long run. After all, Millennials became accustomed to Uber and Lyft, and have stuck with ride-hailing apps even as prices have increased since the start of the pandemic. As students learn to write essays and program computers with the help of AI, they are becoming dependent on the technology. If AI companies can hook young people on their tools now, they may be able to rely on these users to pay up in the future.

Some young people are already hooked. In OpenAI’s recent report on college students’ ChatGPT adoption, the most popular category of non-education or career-related usage was “relationship advice.” In conversations with several younger users, I heard about people who are using AI for color-matching cosmetics, generating customized grocery lists based on budget and dietary preferences, creating personalized audio meditations and half-marathon training routines, and seeking advice on their plant care. When I spoke with Jaidyn-Marie Gambrell, a 22-year-old based in Atlanta, she was in the parking lot at McDonald’s and had just consulted ChatGPT on her order. “I went on ChatGPT and I’m like, ‘Hey girl,’” she said. “‘Do you think it’d be smart for me to get a McChicken?’” The chatbot, which she has programmed to remember her dietary and fitness goals, advised against it. But if she really wanted a sandwich, ChatGPT suggested, she should order the McChicken with no mayo, extra lettuce, tomatoes, and no fries. So that’s what she got.

The Gen Z lifestyle subsidy isn’t entirely like its Millennial predecessor. Uber was appealing because using an app to instantly summon a car is much easier than chasing down a cab. Ride-hailing apps were destructive for the taxi business, but for most users, they were just convenient. Today’s chatbots also sell convenience by expediting essay writing and meal planning, but the technology’s impact could be even more destabilizing. College students currently signing up for free ChatGPT Plus ahead of finals season might be taking exams intended to prepare them for jobs that the very same AI companies suggest will soon evaporate. Even the most active young users I spoke with had mixed feelings about the technology. Some people “are skating through college because of ChatGPT,” Gambrell told me. “That level of convenience, I think it can be abused.” When companies offer handouts, people tend to take them. Eventually, though, someone has to pay up.

Like countless others who have left their hometown to live a sinful, secular life in a fantastic American city, I no longer actively practice Christianity. But a few times a year, my upbringing whispers to me across space and time, and I have to listen. The sound is loudest at Easter, which, aside from being the most important Christian holiday, is also the most fun.

I could talk about Easter all day. The daffodils, the brunch. The color scheme, the smell of grass, the annual screening of VeggieTales: An Easter Carol, which is the same story as Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, except that it’s set at Easter and all the characters are vegetables who work in a factory (the Scrooge character is a zucchini). And most of all, the Easter eggs! Of all the seasonal crafts, this one is the easiest (no carving) and the most satisfying (edible).

This year, because of shocking egg prices, people with online lifestyle brands—or people who aspire to have online lifestyle brands—have suggested numerous ways to keep the dyeing tradition alive without shelling out for eggs. For instance, you can dye jumbo-size marshmallows, or you can make peanut-butter eggs that you then coat in colored white chocolate. You can paint rocks. The story has been widely covered, by local TV and radio stations and even The New York Times. “Easter Eggs Are So Expensive Americans Are Dyeing Potatoes,” the Times reported (though most of the story was about one dairy farmer who’d replaced real eggs with plastic replicas for an annual Easter-egg hunt).

I don’t think many people are actually making Easter spuds. Like baking Goldfish or making breakfast cereal from scratch, dyeing potatoes seems mostly like a good idea for a video to post online. Many Instagram commenters reacted to the Easter potatoes by saying things such as “What in the great depression is this” and “These potatoes make me sad.” And yet, because I love Easter and am curious about the world, I decided to try it myself—just to see if it was somehow any fun.

[Read: I really can’t tell if you’re serious]

My local Brooklyn grocery store didn’t have the classic Paas egg-dyeing tablets, so I bought an “organic” kit that cost three times as much ($6.99) and expensed it to The Atlantic. I bought a dozen eggs ($6.49) and a bag of Yukon Gold potatoes that were light-colored enough to dye and small enough to display in a carton ($5.99), and expensed those to The Atlantic too. Then I looked online for advice on how to proceed; mostly, I wanted to know whether I should cook the potatoes before or after dyeing them. A popular homemaking blog called The Kitchn gave detailed instructions on how to dye Easter potatoes and “save some cash while flexing your creativity for the Easter Bunny this year.” The suggestions—which included soaking the potatoes in ground turmeric, shredded beets, or three cups of mashed blueberries—were not as cost-effective as promised. (Such a volume of fruit could cost north of $15.) But I did find out that I should decorate the potatoes and then cook them. Thank you!

Alone in my kitchen on a Saturday morning, I dyed six boiled eggs and six raw potatoes and used a teensy paintbrush to add squiggly lines, daisies, and other doodles, returning me to my youth as an observant Methodist who really knew her resurrection-specific hymns. The eggs came out in stunning shades of marigold, magenta, and cornflower blue. The potatoes came out sort of yellow, or sort of pink, or sort of purple, all of which you may recognize as colors that potatoes already have when you buy them at the store. I hated them.

When I painted HAPPY EASTER on one of the potatoes, it looked like a threat. When I baked them in my oven, their skins (naturally) crinkled and came somewhat unstuck from their insides. This had the effect of making them look shriveled and even more sinister. When I put them in the egg carton next to my beautiful half-dozen Easter eggs, I thought: Only a person who was lying would do this and say it was good. Without being too overwrought about it, the whole project felt like a symbol not of renewal but of the wan stupidity of our cultural moment.

[Read: The case for brain rot]

The average price for a carton of eggs last month was $6.23, which is, we all agree, a lot for eggs. But it’s not really a lot for a craft project that also serves as a cultural ritual and can also serve as breakfast, so long as you put your craft project and cultural ritual in the refrigerator. (Until recently, I’d assumed that all families eat their Easter eggs, but apparently some people put them on display in their house, after which you certainly can’t eat them.) Sure, if an egg is really too expensive, replacing it with a potato could be called ingenious. But the many deficiencies of this replacement are immediately obvious. For instance, dye doesn’t work as well on a brown potato as it does on a white egg. Potatoes are uninspiring objects—people evoke them when they want to suggest that something is lumpy, dumb, or useless. Eggs are lovely, smooth, elegant, and the subject of fine art. Eggs are revered. You can’t just swap one thing out for another because they are a similar size and weight.

I know I am being judgmental—decidedly not the point of Easter. But this insincere hack rudely assumes that children can’t tell the difference between a simple, nice thing and a more complicated, far inferior thing. I will concede only one point to the potato-dyers. As The Atlantic put it rather grotesquely in 1890, eggs symbolize “the bursting into life of a buried germ.” I have to admit that this is a pretty good way to describe tubers as well. It made me briefly consider burying my Easter potatoes in the backyard and waiting to see if they would grow into more Easter potatoes. Season of hope and all that.

[From the May 1890 issue: The Easter hare]

Instead, I ate all of them and then they were gone, which felt a lot better.

Josh Shapiro is very lucky to be alive. The Pennsylvania governor and his family escaped an arson attack in the early hours of this morning. Parts of the governor’s mansion were badly charred, including an opulent room with a piano and a chandelier where Shapiro had hosted a Passover Seder just hours earlier. Things could have been much worse. The suspect, Cody Balmer, who turned himself in, would have beaten Shapiro with a hammer if he had found him in his home, he reportedly said in an affidavit.

Balmer admitted to “harboring hatred” of Shapiro, authorities said, but his precise motives are still unclear. He reportedly expressed anti-government views and made allusions to violence on social media. He reposted an image of a Molotov cocktail with the caption “Be the light you want to see in the world.” Balmer’s mother told CBS that he has a history of mental illness. But no matter how you square it, the attack is just the latest example of political violence in the United States. Last month, a Wisconsin teenager was charged with murdering his mother and stepfather as part of a plot to try to assassinate President Donald Trump—this, of course, follows two assassination attempts targeting Trump last year. Other prominent instances of ideological violence include the murder of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson late last year, and the time when a man broke into Nancy Pelosi’s home in 2022 and attacked her husband, Paul Pelosi, with a hammer, fracturing his skull. (He was badly hurt but survived.)

Shapiro is a Democrat, but in a rare moment of bipartisan agreement, Republicans joined Democrats in condemning the attack. President Trump said in the Oval Office today that the suspect “was probably just a wack job and certainly a thing like that cannot be allowed to happen.” Vice President J. D. Vance called the violence “disgusting,” and Attorney General Pam Bondi posted on X that she was “relieved” that Shapiro and his family are safe.

These kinds of condemnations of political violence are good. They’re also meaningless—especially when taken in the broader context of Trump’s governing style. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that since Trump first ran for office, political violence has been on the rise. When it’s useful to Trump, he praises violence and makes leveraging the threat of it endemic to his style of politics. When Montana’s then–congressional candidate (and now-governor) Greg Gianforte assaulted a reporter in 2017, Trump later said, “Any guy that can do a body slam, he is my type!” After Kyle Rittenhouse shot and killed a protester in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in the summer of 2020, he had a friendly meeting with Trump at Mar-a-Lago the next year. And during a presidential debate against Joe Biden that fall, when Trump was asked if he would rebuke the Proud Boys, a far-right organization with a history of inciting violence, he told the group to “stand back and stand by,” as though he were giving it orders. (This is also how the Proud Boys interpreted it.)

Read: A brief history of Trump’s violent remarks

Trump made his willingness to engage in political violence especially clear during the Capitol insurrection on January 6, 2021. Instead of immediately attempting to call off his rabid supporters, Trump sat on his hands as his supporters stormed the Capitol—even as members of his own party urged him to help. Despite having lost the election, Trump appeared okay with violence if it helped him maintain the presidency.

Since retaking office, Trump has appeared to continue this tradition. When Pete Hegseth, the president’s pick for secretary of defense, faced a sexual-assault accusation ahead of his confirmation vote, violence may have been the ingredient that ensured that Trump got his way. Republican Senator Thom Tillis seemed concerned that some of the allegations against Hegseth could be credible and was on track to tank his nomination. According to Vanity Fair, the FBI warned Tillis of “credible death threats” against him, which could have played a role in his decision to back down. Tillis has not said whether the death threats influenced his Hegseth vote, but his office released recordings of the threats he has received.

Other Republicans in Congress are afraid of opposing Trump because of similar potential concerns for their safety. Many have gone on the record in recent years and said as much. Mitt Romney told my colleague McKay Coppins that a fellow congressman confessed to him that he had wanted to vote for Trump’s second impeachment in 2021 but ultimately chose not to out of fear for his family’s safety. That same year, Republican Representative Peter Meijer told my colleague Tim Alberta that he witnessed a fellow member of Congress have a near breakdown over fear that Trump supporters would come for his family if he voted to certify the 2020 election results.

All of this is to say that when Trump condemns acts of political violence, it’s impossible to take him seriously. In this specific case, the attack on Shapiro served no clear benefit to Trump, which is why he was able to so quickly speak out against it. Compare that with how he’s talked about the Pelosi hammer attack, which he has used as fodder to mock the Pelosis. Trump’s relationship to political violence is the same as his relationship to anything and anyone else in his orbit: If something benefits him, it’s welcome. If not, he may dismiss it.

Nearly three months into President Donald Trump’s term, the future of American AI leadership is in jeopardy. Basically any generative-AI product you have used or heard of—ChatGPT, Claude, AlphaFold, Sora—depends on academic work or was built by university-trained researchers in the industry, and frequently both. Today’s AI boom is fueled by the use of specialized computer-graphics chips to run AI models—a technique pioneered by researchers at Stanford who received funding from the Department of Defense. All of those chatbots? They rely on a training method called “reinforcement learning,” the foundations of which were developed with National Science Foundation (NSF) grants.

“I don’t think anybody would seriously claim that these [AI breakthroughs] could have been done if the research universities in the U.S. didn’t exist at the same scale,” Rayid Ghani, a machine-learning researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, told me. But Trump and the Department of Government Efficiency have frozen, canceled, or otherwise slowed billions of dollars in grants and fired hundreds of staff from the federal agencies that have funded the nation’s pioneering academic research for decades, including the National Institutes of Health and the NSF. The administration has halted or threatened to withhold billions of dollars from premier research universities that it has accused of anti-Semitism or unwanted DEI initiatives. Graduate students are being detained by immigration agents. Universities, in turn, are issuing hiring freezes, reducing offers to graduate students, and canceling research projects.

Outwardly, Trump has positioned himself as a champion of AI. During his first week in office, he signed an executive order intended to “sustain and enhance America’s dominance in AI” and proudly announced the Stargate Project, a private venture he called “the largest AI infrastructure project, by far, in history.” He has been clear that he wants to make it as easy as possible for companies to build and deploy AI models as they wish. Trump has consulted and associated himself with leaders in the tech industry, including Elon Musk, Sam Altman, and Larry Ellison, who have in turn showered the president with praise. But generative AI is not just an industry—it is a technology dependent on progressive innovations. Despite his bravado, Trump is rapidly eroding the engine of scientific innovation in America, and thus the capacity for AI to continue to advance.

In a statement, White House Assistant Press Secretary Taylor Rogers wrote that the administration’s actions are in service of building up the economy, fighting China, and combatting “divisive DEI programs” at the nation’s universities. “While Joe Biden sat back and let China make gains in the AI space, President Trump is restoring America’s global dominance by imposing tariffs on China—which has ripped us off for far too long,” Rogers wrote. (As my colleague Damon Beres wrote earlier this week, tariffs may only hurt American technology businesses.)

Despite Trump’s aims, the United States now risks losing ground to Canada, Europe, and, indeed, China in the race for AI and other technological innovation. In a Nature poll of American scientists last month, 75 percent of respondents—some 1,200 researchers—said they were considering leaving the country. New scientific and technological developments may occur elsewhere, slow down, or simply stop altogether.

Silicon Valley, despite frequently operating at odds with federal oversight, could not have come up with some of its most valuable ideas, or trained the research scientists who did, without the government’s assistance. Federally supported research and researchers, conducted and trained at American universities, helped make possible the internet, Google Search, ChatGPT, AlphaFold, and the entire AI boom (to say nothing of vaccines, electric vehicles, and weather forecasting). This fact is not lost on two of the “godfathers” of AI, Yann LeCun and Geoffrey Hinton, both of whom have lambasted the administration’s assault on science funding.

[Read: Throw Elon Musk out of the Royal Society]

“Curiosity-driven research is what allows us to explore directions that venture capital or research labs in industry would not, and should not, explore,” Alex Dimakis, a computer scientist at UC Berkeley and a co-founder of the AI start-up Bespoke Labs, told me. For example, AlphaFold—a series of AI models that predict the 3-D structure of proteins—was designed at Google but trained on an enormous collection of protein data that, for decades, has been maintained with funding from the NIH, the NSF, and other federal agencies, as well as similar government support in Europe and Japan; AlphaFold’s creators recently won a Nobel Prize. “All of these innovations, whether it’s the transformer or GPT or something else like that, were built on top of smaller little breakthroughs that happened earlier on,” Mark Riedl, a computer scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology, told me. Needing to show investors progress each fiscal quarter, then a source of revenue within a few years, limits what topics scientists can pursue; meanwhile, federal grants allow them to explore high-risk, long-term ideas and hypotheses that may not present obvious paths to commercialization. The largest tech companies, such as Google, can fund exploratory research but without the same breadth of subjects or tolerance for failure—and these giants are the exception, not the norm.

The AI industry has turned previous, foundational research into impressive AI breakthroughs, pushing language- and image-generating models to impressive heights. But these companies wish to stretch beyond chatbots, and their AI labs can’t run without graduate students. “In the U.S., we don’t make Ph.D.s without federal funding,” Riedl said. From 2018 to 2022, the government supported nearly $50 billion in university projects related to AI, which at the same time received roughly $14 billion in non-federal awards, according to research led by Julia Lane, a labor economist at NYU. A substantial chunk of grant money goes toward paying faculty, graduate students, and postdoctoral researchers, who themselves are likely teaching undergraduates—who then work at or start private companies, bringing expertise and fresh ideas. As much as 49 percent of the cost of building advanced AI models, such as Gemini and GPT-4, goes to research staff.

“The way in which innovation has occurred as a result of federal investment is investments in people,” Lane told me. And perhaps as important as federal investment is federal immigration policy: The majority of top AI companies in the U.S. have at least one immigrant founder, and the majority of full-time graduate students in key AI-related fields are international, according to a 2023 analysis. Trump’s detainment and deportation of a number of immigrants, including students, have cast doubt on the ability—and desire—of foreign-born or -trained researchers to work in the United States.

If AI companies hope to bring their models to bear on scientific problems—say, in oncology or particle physics—or build “superintelligent” machines, they will need staff with bespoke scientific training that a private company simply cannot provide. Slashing funding from the NIH, the NSF, and elsewhere, or directly withdrawing money from universities, may lead to less innovation, fewer U.S.-trained AI researchers, and, ultimately, a less successful American industry. Meanwhile, multiple Chinese AI companies—notably DeepSeek, Alibaba, and Manus AI—are rapidly catching up, and Canada and Europe have sizable AI-research operations (and healthier government science funding) as well. They will simply race ahead, and other companies could even relocate some of their American operations elsewhere, as many financial institutions did after Brexit.

If the pool of talented AI researchers shrinks, only the true AI behemoths will be able to pay them; as the pool of federal science grants dwindles, those same firms will likely further steer research in the directions that are most profitable to them. Without open academic research, the AI oligopoly will only further cement itself.

That may not be good for consumers, nor for AI as a scientific endeavor. “Part of what has built the United States into a real juggernaut of research and innovation is the fact that people have shared research,” Alondra Nelson, a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study who previously served as the acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, told me. OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google share limited research, code, or training data sets, and almost nothing about their most advanced models—making it difficult to check products against executives’ grandiose claims. More troublingly, progress in AI—and really any technology or science—depends on collaboration among people and pollination of ideas. These firms could plow ahead with the same massive, expensive, and energy-intensive models that may not be able to do what they promise. Fewer and fewer start-ups and academics will be able to challenge them or propose alternative approaches; these firms will benefit from fewer and fewer graduate students with outside perspectives and expertise to spark new breakthroughs.

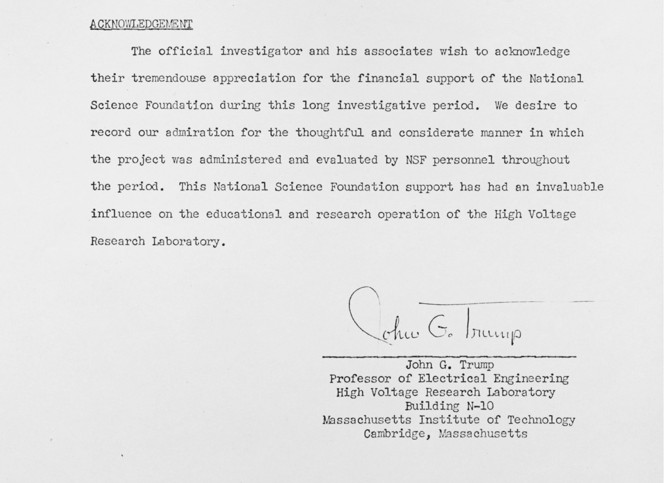

President Trump may not care much for these scientists. But there is one he holds in high esteem who might have had something to say about all this. The president’s late uncle, John G. Trump, was a physicist at MIT who did pioneering work in clinical and military uses of radiation. The president has called Uncle John a “super genius.” John Trump received a national medal of science from the NSF, and his work was supported by at least hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants from the agency—more than $4 million today—in addition to funding from the NIH, according to his papers in the MIT archives and government reports. Those NSF grants supported at least six doctoral, 20 master’s, and 13 undergraduate theses in Trump’s lab—and that was one 14-year period in the elder Trump’s decades-long career.

As I did research for this article, I found the scientist’s final research report to the NSF upon the conclusion of those 14 years, written in 1966.

John G. Trump took care to note his team’s “tremendouse [sic] appreciation for the financial support of the National Science Foundation” and its “admiration for the thoughtful and considerate manner in which the project was administered and evaluated by NSF personnel.” The foundation’s support, Trump said, had been an “invaluable influence on the educational and research operation” of his lab. Almost 60 years later, education and research no longer seem to be among the nation’s priorities.

The madness started, as baseball madness tends to start, with the New York Yankees: At the end of March, during the opening weekend of the new season, the team’s first three batters hit home runs on the first three pitches thrown their way. The final score, 20–9, was almost too good to be true. And then, everybody noticed the bats.

A handful of Yankees had used unconventional instruments to hit their home runs: Their bats bulged out a little near the end, such that they were shaped more like bowling pins than clubs. It turned out they’d been designed by an MIT-trained physicist and were tailored to each player’s swing, with the bulge positioned at the place on the bat where that player tends to hit the ball. Yes, after at least a century’s worth of baseball bats that all looked more or less the same—“it must be made of wood, and may be of any length to suit the striker,” reads a set of rules from 1861—the art of making striker’s wood had at last produced a major innovation. After the Yankees hit a franchise-record nine home runs in that one game, media coverage of torpedo bats exploded, and manufacturers are struggling to meet demand from other teams. Even fantasy baseball leagues have cottoned to the trend. “This is torpedomania,” said the CEO of a major bat maker.

At first glance, the craze appears to be the culmination of the data-driven tweaks that have overhauled the modern game. A pursuit of minute statistical advantages characterizes nearly every aspect of baseball today: Pitchers maximize effectiveness by throwing the ball as hard as possible, and rarely spend more than five innings in a game; managers eschew traditional—and suboptimal—strategies such as bunting and stealing bases; fans obsess over esoteric performance metrics with names such as “wRC” and “xFIP.” Now the data revolution is reimagining one of the game’s most fundamental tools: the bat.

The idea of the bowling-pin shape is actually a few years old and has been explored by multiple teams. Aaron Leanhardt, the aforementioned MIT physicist, began designing the Yankees’ torpedo bats in 2022 as a minor-league hitting coach for the team, and some major leaguers were using them last year. His premise was straightforward: Standard bats are widest and heaviest at the tip, but players prefer to make contact with a pitch closer to the midpoint. That’s in part because a bat’s “sweet spot”—the portion of the wood that transfers the most energy on contact—is also a few inches down the barrel from the end. To address this inefficiency, torpedo bats are made with more wood in the sweet spot and less wood elsewhere—thus, the bulge. The idea was to “put it where you’re trying to hit the ball,” Leanhardt told The Athletic.

But that premise may be suspect. Despite their Moneyball makeover, torpedo bats remain, for now, a blunt instrument, largely superstition with a patina of data. Though it seems like common sense that adding heft to the part of the bat where a player hits the ball would be advantageous, several physicists who study baseball bats told me that’s not necessarily true. Because a bat has a thick barrel and rotates when swung, its motion and power depend on the distribution of weight across the entire shaft, not just in one spot. In other words, the physics aren’t cut-and-dried: A bulging sweet spot may provide more space for making contact with the ball, but it likely won’t provide more power. (The Miami Marlins, for whom Leanhardt now works as a field coordinator, declined a request for comment.)

[Read: Why aren’t women allowed to play baseball?]

All of the mass along a bat’s barrel, not just at the point of contact, contributes to the impact. As a result, shifting some wood from the end of the barrel to the sweet spot will not make the bat more powerful, Lloyd Smith, a mechanical engineer who studies ball-bat collisions at Washington State University, told me. Brian Hillerich, the director of professional bat production at Hillerich & Bradsby Co., which makes bats for Louisville Slugger, said that even if torpedo bats are not more powerful, they still promote more consistent contact at the sweet spot, which would tend to help a player’s performance. Smith and other physicists said this is possible, but remains unproved.

In any case, by redistributing some mass closer to the handle, the bowling-pin design could actually make a bat feel lighter when swung—it could lower the “moment of inertia,” in physics parlance. That will allow a player to increase his bat speed, but it also shrinks the force he can apply upon contact. These two factors may well cancel out, Dan Russell, a physicist at Penn State who studies baseball-bat vibrations, told me. (Imagine swinging a hammer while gripping its head instead of its handle: It might move faster, but it wouldn’t do a better job of pounding nails.) A torpedo bat could also be constructed by adding extra wood to make the bulge instead of merely shifting it from other places on the barrel. This would keep the “moment of inertia” constant—the bat would be heavier on a scale but feel the same when swung. Baseball bats used to have more heft as a rule; Babe Ruth swung clubs perhaps 50 percent heavier than today’s. But the net effects remain unclear, and would depend on each particular player’s strength and swing.

A faster swing could still be useful even if it doesn’t give a hitter greater power: “You simply have better bat control, can wait a little longer on the pitch before deciding to swing, make adjustments once you’ve started,” Alan Nathan, who studies the physics of baseball at the University of Illinois, told me. That won’t be the case for everyone—athletes who have spent years honing their swings and timing could be thrown off by the new shape, and several players using torpedo bats have had terrible starts to this season. Hillerich told me that his company designs torpedo bats with this in mind, trying to make them feel as similar to a player’s original bat as possible. It might all be a matter of preference and confidence—and others may not care that much either way. The new shape feels the same in his hands, Jazz Chisholm, a torpedo-wielding Yankee, recently said. “I don’t know the science of it. I’m just playing baseball.”

That the Yankees had a historically great game, and that some players were using funny-looking bats, “is more coincidence than destiny or science,” Smith told me. After all, nobody noticed the new shape last season, and for good reason—there’s simply not enough information, either from MLB games or physics labs, to definitively say what these bats offer, and to which players. Smith said he suspects that “the number of athletes this torpedo bat benefits is going to be fairly narrow.”

Indeed, the current buzz about the bats is pretty much the opposite of being data-driven. In an interview last week with The Athletic, Brett Laxton, the lead bat maker at Marucci Sports, pointed to the fact that Giancarlo Stanton, the Yankees’ designated hitter, had hit three home runs in his first game using a torpedo bat last year. That was “a good eye test” of the technology, he said, invoking just the kind of baseball intuition that statistics-driven analysts would sneer at. Yes, the bat felt and looked good in Stanton’s hands; no, this is not sabermetrics. Meanwhile, other “eye tests” have yielded more ambiguous results. Elly de la Cruz, of the Cincinnati Reds, hit two home runs in his first game using the torpedo bat, for instance, then went 0–4 the next day. Max Muncy, of the Los Angeles Dodgers, tried using a torpedo bat and recorded three outs in a row, then switched back to his old wood and hit a game-tying double.

If anything, the torpedo bats harken to an era before Moneyball, computers, or even the official formation of Major League Baseball. The late 1800s were a time of “great experimentation” in bat design, John Thorn, MLB’s official historian, told me: four-sided bats and flat bats, bats with slits for springs and sliding weights. All of that tinkering has long been left behind, however, and the modern, non-torpedo bat now seems like a simple fact of the game. Perhaps the biggest change to bat manufacturing in recent decades happened in the 1990s, when Barry Bonds started swinging bats made from maple instead of ash, and the rest of the league followed. That, too, had an element of superstition: As it turns out, a bat made from maple wood transfers a little bit less energy to a ball than one made from ash. Bonds, who hit more home runs than any MLB player in history, “could have hit the ball just a bit further if he had stayed with ash,” Smith told me.

Thorn takes issue with the whole discussion. “The whole idea that the magic is in the bat rather than in the batter is fraud,” Thorn said. “It’s calumny.” Of course, baseball players and fans have always been in pursuit of magic. They once used less pretentious tricks—eating chicken before each game, wearing a gold thong to emerge from a funk—but these have now been funneled through the optimization craze; instead of mismatched socks, there are “literal genius”–designed bats. In an era when baseball teams will squeeze any source of data for tiny statistical advantages, torpedomania pretends to be yet another nerd-ish secret weapon. Perhaps, for some subset of players, the new design really is miraculous. More likely, though, when the stats have all been counted and compared, we’ll discover that the torpedo bat is no different from any other talisman in baseball: a ridiculous distraction; a delightful waste of time.

Sign up for Trump’s Return, a newsletter featuring coverage of the second Trump presidency.

To plainly state what is going on right now would make you sound delusional.

The president of the United States has essentially been holding the global financial system hostage. He’s done so by threatening massive tariffs on nearly 100 countries and territories, including one that is unpopulated. These tariffs, which were set to go into effect today but have now been put on a 90-day pause for every country except for China, which will see a 125 percent tax on exports, seem to have been calculated using a blanket formula that some economists and trade experts find almost nonsensical. (Many have speculated that the math was done by a chatbot.) The administration’s supporters do not have a coherent message about why any of this is happening; before President Donald Trump announced the pause, they’d argued simultaneously that the tariffs were a temporary negotiating tactic but also that they might be durable enough to bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States.

As the world braced for Trump’s tariffs to go into effect, stocks plummeted, wiping out trillions of dollars in value. The price of government bonds also dropped precipitously, triggering genuine fear of a dangerous debt crisis. Wall Street analysts likened the tariffs to a U.S. tax increase of roughly $660 billion; one economist called it a set of “punishing sanctions against the American people.” The situation is volatile: 10 percent universal tariffs are still in place, inflation remains a concern, America is still in a trade war with China, and it’s not at all clear that Trump will not just repeat this act as we approach the 90-day deadline.

For many, the second Trump administration has felt like a constant tearing of the fabric of our reality. The country is facing a deadly measles outbreak after Congress confirmed Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a man with a profound skepticism of modern medicine, to run the Department of Health and Human Services. For a time, the businessman Elon Musk seemed to be acting as a shadow president, and he’s participated in the gutting of the federal government (when he’s not streaming himself playing video games on social media). ICE has apprehended visa-holding students off the street—sometimes for no clear reason at all.

While many of these acts have been ignored or rationalized by the president’s supporters, the tariffs may be different. Can the culture war—largely powered by memes, ideologies, vibes, and extremely online radicalization—survive the harsh reality of a trade war? The pause is only temporary; if Trump does not relent, he might still cause a financial meltdown. Trump has also destroyed a lot of trust—just the possibility of future tariffs may cause enough uncertainty to hurt businesses and investors. This would be the ultimate stress test of people’s otherwise unshakable devotion to the president—a final gantlet for this MAGA delusion.

Tech leaders and venture capitalists who have cozied up to Trump were already harmed by the threat of tariffs. Their stock prices are down, and the broad duties planned by the administration will severely affect supply chains, making core products such as smartphones more expensive. (The 125 percent tax on Chinese exports that remains might still have this effect.) There’s genuine concern that the entire industry could be set back years as the uncertainty caused by Trump’s erratic decision making hinders the building of supercomputers as well as strategic investments by VCs. One analyst called it an “economic armageddon” for the industry.

[Read: Buy that new phone now]

Although none of the big technology companies have issued a public statement against the tariffs, some cracks have begun to show. Musk, an administration loyalist, has made personal appeals to Trump to reverse course and used his platform on X to repeatedly insult Peter Navarro, one of the architects of the tariffs, calling him “dumber than a sack of bricks” and giving him the nickname “Peter Retarrdo.” A few other pro-Trump investors and entrepreneurs have issued their own frustrations: The Palantir co-founder Joe Lonsdale tepidly critiqued the rollout, suggesting that “the tariffs could be done better.” Others have indicated that they were misled by enthusiasm for Trump’s culture warring.

Bill Ackman, the billionaire hedge-fund manager and ardent Trump supporter, might have offered the best example of buyer’s remorse on Sunday, when he posted on X that the tariffs were the equivalent of an “economic nuclear war.” He posited that the United States “will severely damage our reputation with the rest of the world that will take years and potentially decades to rehabilitate.” Later, he admitted that he’d underestimated Trump’s penchant for chaos. “I don’t think this was foreseeable,” he posted, referring to the tariffs Trump touted throughout his campaign. “I assumed economic rationality would be paramount. My bad.” The contrition didn’t last: After the pause was announced, Ackman posted on X, “This was brilliantly executed by @realDonaldTrump. Textbook, Art of the Deal.” As of this writing, there is no evidence from the White House that Trump received any specific concessions from the tariffed nations; he merely created a crisis and then paused it because the world (and markets) got spooked. “People were getting a little bit yippy,” Trump told reporters this afternoon.

[Jonathan Chait: Trumpworld makes the case against Trump]

Just as notable are the justifications from the far-right influencers who have served as a de facto propaganda arm for the White House. As markets tanked last week, they swiftly argued in favor of broad austerity measures as a necessary hardship, suggesting that Americans do “not need” consumer electronics such as cellphones and video-game consoles and that American lives have not been changed by the tariffs. Benny Johnson, a Trump loyalist, social-media personality, and podcast host, went further: “Losing money costs you nothing,” he said on his podcast. “In fact, you learn a lot of lessons actually by losing money. Losing your character costs you everything. Losing your country loses you everything.” Other MAGA devotees and some Fox News hosts have conscripted tariffs into the culture wars, justifying them as helping to fix the country’s “crisis in masculinity.”

It’s not just the shock jocks. On X, entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and a faction best described as an anti-woke tech commentariat posted long threads, proclaiming the tariffs a Trumpian masterstroke. Chamath Palihapitiya, a venture capitalist and one of the hosts of the All-In podcast, recently hypothesized that Trump would bring world leaders to Mar-a-Lago to remake the world economy in what Palihapitiya referred to as “Bretton Woods 2.0.” Keith Rabois, a well-known tech investor, declared that “Trump Derangement Syndrome has morphed into Tariff Derangement Syndrome,” suggesting that the slew of economists and trade experts horrified by the administration’s proposal are all wrong. “I would believe in any macro trader w sustained returns for decades over any academic,” he wrote.

This combination of blind faith, reactionary ideology, and endless justification have less in common with any kind of politics and policy than they do with genuine conspiratorial thinking—a kind of QAnon 2.0 for finance. As in QAnon, a sprawling network of conspiracy theories about a nefarious cabal referred to as the “deep state,” Trump is made out to be a hero, pulling the strings and playing multidimensional chess to deliver political salvation to his devotees. QAnon’s earliest prediction, back in 2017, revolved around Trump “removing criminal rogue elements,” including arresting Hillary Clinton. But the broader goal was a dismantling of the New World Order. The arrests never came, but the elaborate predictions continued. QAnon became a cult in which followers were given “crumbs” and told to “trust the plan.” The group’s slogan was an admission of total surrender to the conspiracy: “Where we go one, we go all.”

It’s not a perfect one-to-one comparison, but many of the dynamics are quite similar. Both QAnon and the legion of tariff true believers share an unabiding faith in Trump, ascribing his erratic governing style to a master plan. As my colleague Adrienne LaFrance wrote in 2020, in QAnon, “every contradiction can be explained away; no form of argument can prevail against it.” Similarly, ardent supporters of Trump’s tariffs have refused to see any of the plan’s glaring flaws: Fluctuations in the stock market are dismissed as not real or, in some cases, a good thing, because they hurt the “bastards” on Wall Street. Either the sell-off is part of a necessary cleansing of the American economy or it’s a blip, the result of Trump playing chicken with world leaders. In some cases, supporters argue that the stock market has almost nothing to do with the long-term health of the economy at all. To these people, the notions that the tariffs will hurt the working-class families they’re supposed to liberate and that they could halt the domestic manufacturing they’re supposed to energize are distractions seeded by an enemy who doesn’t want you to see the end game.

But above all, the prime directive for both QAnon and the tariff truthers is the same: Trust the process. The tech investor and Trump supporter Shaun Maguire wrote on X last week that the tariffs are better than maintaining the status quo: “Stay the course and have a 100% chance you lose in 20 years…Or do the hard things and have a 70% chance you win.” These numbers, it’s worth noting, appear to be random, but they represent a kind of unflinching devotion to a plan that doesn’t seem to exist. Trump, taking a page from Q’s book, issued his own version of this message on Monday, telling supporters on social media, “Don’t be Weak! Don’t be Stupid! Don’t be a PANICAN (A new party based on Weak and Stupid people!).” In response, Fox News ran a lower-third banner with the phrase Good Things Come To Those Who Wait. On X, far-right influencers began using Trump’s term—Panican—as a way to dismiss earnest criticism and concerns about the tariffs. Just as QAnon offered promises of a Great Awakening, in which the deep state was vanquished and the truth of the evils of the global elite cabal was revealed, the tariffs also offer the promise of an imagined utopia. The far-right activist Jack Posobiec summed up the attitude best on X on Monday: “My own retirement account is down too … Don’t care … All-in on the Great Deal … The Golden Age is on the other side.”

The TariffAnon crowd is right about one thing: Even the near future is deeply uncertain. As I wrote these words, the market rallied (the Panicans were fools all along!), only to lose all gains a few hours later (the Panicans are making too big a deal out of market fluctuations). After announcing his pause, Trump confusingly also said that the U.S. would apply additional 10 percent tariffs to Canada and Mexico. It remains possible that Trump could successfully negotiate a bunch of trade deals, placating the markets and further cementing him as a hero among his base. Or it could all go disastrously.

Some political observers hope that Trump single-handedly inflicting deep financial pain on the world might break the spell among his most ardent supporters. In this way, the tariffs are a reality test. But if the recent past is any guide, what many dismiss as bad-faith rhetoric can quickly harden into a core ideology for a set of true believers; the anti-vax movement and the subsequent measles outbreaks are a sobering analogue. This is how breaks with reality occur now, aided, in part, by the internet’s justification machine, which is an efficient mechanism for dispelling any trace of cognitive dissonance. In some cases, falling down the conspiratorial rabbit hole is motivated by grievance—my enemies hate this, therefore it must be good. And any market bounce-back after Trump’s announcement of a 90-day pause will be taken by true believers as evidence of the president’s genius (see: Bill Ackman).

Some Trump supporters are also worried about their reputations. For many outspoken VCs, backing Trump was a bet, much like investing in a portfolio company—one that came with substantial risk. Should Trump’s tariff scheme backfire completely by causing a recession or worse, their reputations as risk managers and complex-systems thinkers would naturally be tarnished (see: Bill Ackman). Unless, of course, they chose to double down and create a fictional narrative in which they cannot be wrong. The truthers are, in essence, talking up their reputational investment —as if the Trump administration was a stock they were holding. As Trump himself has proved throughout his political career, it is often easier to double down and build a fantasy world around your mistake than to admit you were wrong.

That sufficiently motivated people might break with reality is by now somewhat predictable in American politics. But what’s far more uncertain is what happens when reality punctures the protective bubble of cognitive dissonance. QAnon devotees and MAGA die-hards were certain that Trump won the 2020 presidential election. When reality became impossible to ignore, we got January 6. Few events have the power to pierce the veil, but a global financial crisis could be one of them. What happens if the true believers are confronted with a truth they can’t look away from? History suggests it won’t go well.

The tariff apocalypse is upon us. Should you buy an iPad?

Some people, it seems, have answered with a resounding yes. Bloomberg reported yesterday that at some Apple stores, “the atmosphere was like the busy holiday season.” Fearing that the price of electronics will increase as a result of President Donald Trump’s tariffs, people are rushing to purchase stuff. If the economy must collapse, at least let it do so after you have obtained a new tablet for $599 plus tax.

The panic-buying is a little funny. First, because if we are on the eve of a global recession, we have bigger things to worry about than new gizmos. Second, because we are still in the haze of a Trump pseudo-reality. The major tariffs will not hit until tomorrow, assuming there isn’t some unexpected reversal in the next several hours, and no one knows for certain how any of this will shake out.